What Makes Humans Special?

"No truth appears to me more evident than that beasts are endow’d with thought and reason as well as men." ~ David Hume

Until recently, when the revered intellectuals of the Western tradition looked around at the animal kingdom, they confidently declared humanity unique. All animals differ from one another, of course, but these thinkers insisted that humans are categorically distinct. Humans, they tell us, possess something that animals do not. Once you inquire further as to what exactly that thing is, agreement starts to break down.

Plato and Aristotle acknowledged that humans share many physical and even psychological characteristics with animals. We shun what is bad for us and pursue what is good for us, or at least what we think is good for us. We want to live, experience pleasure, and reproduce. We don’t want to die or experience pain. But for these philosophers, the blessing and burden of humanity is that there’s more to it than that.

Of all terrestrial creatures, humans have “souls” capable of perceiving and participating in the divine logos, cosmic reason. Humans are able to look through the mere appearances of things, the phenomena that parade moment by moment across the senses, to discover their true natures. For Aristotle, this is not an optional ability that people may or may not choose to enjoy. It is the telos, the highest or final purpose, for which humans exist. Each person actualizes their humanity to the extent that they orient themself toward acquiring theoretical knowledge.

This uniquely human form of reason, the ancients tell us, is the ground of free will and the ethical life. We are the only creatures that deliberate over which goals are worth pursuing. Then we must actually choose to follow through on pursuing them. The fact that we must deliberate about and choose how to relate to other humans opens up a space for ethics. Finally, reason makes us vulnerable to persuasion, the foundation of proper human political life.

As Greek philosophy was incorporated into the juggernaut of Christianity, this understanding of human nature remained mostly intact. The Christian philosophers used the phrase “the image of God” to speak about human uniqueness, but they largely agreed that it consisted in some combination of reason, free will, and moral agency. They glossed the philosophical language theologically, agreeing that human reason’s ultimate object is The True and the will’s ultimate object is The Good, so long as both of those were understood to be God. Finally, somewhat sheepishly contradicting Aristotle on this point, they declared that human souls are immortal and separable from their respective bodies.

Monkey Man?

Everyone seemed content with this framework until Darwin’s The Descent of Man reopened the question of how unique humans really were. He asked the Victorians, who would have been appalled to find out about a previously unknown criminal or Catholic relation, to redraw their genealogical trees to include every living creature, all the way back to some single-cell blob in a primordial ocean. [For my article on Darwin, including his thoughts on human uniqueness, see here.]

To assuage their wounded pride, some fell back on dogma. Others simply gestured vaguely at everything. We have cities and locomotives and factories and art and literature! Biblical literalists and fashionable skeptics alike pointed to clothing as a dividing line. But doubts lingered. If human reason is the result of evolution, can it really be categorically distinct from animal intelligence? And how intelligent are animals, anyway?

Frans de Wall, a primatologist who spent his career ethics in animals, pointedly reversed the question. His book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? raised the criticism that speaking of intelligence in the singular already misrepresents the many dimensions of cognition and may blinker us to faculties outside our own experience.

The last century of research, some of which focused on close observation of animals in their natural habitats, some on tightly controlled experiments, has disclosed an astonishing array of intelligences. Countless times, received opinion that surely animals couldn’t do X was overturned by some species or other doing X.

To give one example, while humans easily recognize each other on sight, humans are not always able to recognize individual animals on sight. The individuals of many species look more or less alike to humans. So, it was assumed that animals also couldn’t tell each other apart. But in many cases this is simply false. Apes and monkeys can recognize faces of their own kind and of humans; paper wasps can recognize each others’ faces; sheep recognize each other; crows not only recognize individual humans but also remember how those humans treated them.

Likewise, for quite some time, it was confidently stated that only humans can use tools. But apes regularly repurpose items in the environment as tools. So do elephants. Apes can fabricate new tools to solve problems. More impressively, some, such as chimpanzees in Gabon hunting honey, combine multiple tools into a burglar’s toolkit:

These chimps raid bee nests using a five-piece toolkit, which includes a pounder (a heavy stick to break open the hive’s entrance), a perforator (a stick to perforate the ground to get to the honey chamber), an enlarger (to enlarge an opening through sideways action), a collector (a stick with a frayed end to dip into honey and slurp it off), and swabs (strips of bark to scoop up honey).

Tool usage isn’t even the exclusive domain of mammals. Crows will drop rocks into a tube of water to raise the water level, bringing floating food within reach. Crows can also solve multi-step problems, such as retrieving a short stick in order to reach a longer stick, which will in turn allow it to reach some meat. More examples of intelligence may lie in places more difficult to observe. Veined octopuses off the coast of Indonesia sneak across the sea floor collecting coconut shells, which it will at some later time assemble into a camouflage shelter.

Still, it does seem that there are some things that humans are uniquely good at. Although many species communicate in various ways, only humans have language in the sense of open-ended, flexible, recursive syntax. Human social relationships are considerably more complex than any observed in the animal kingdom. We may have unique instincts regarding morality.

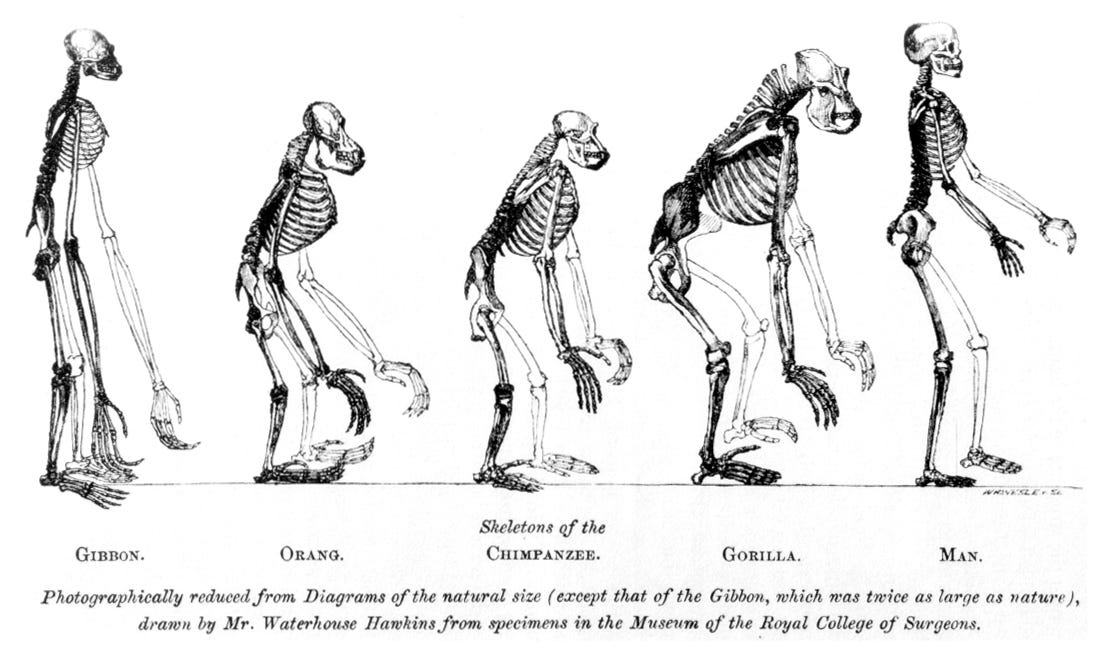

If we grant that humans are in some ways unique, we still need to seek an evolutionary explanation for this abilities. Since the human brain is “a linearly scaled-up primate brain” with no unique anatomical features, our capacities must be developments and extensions of primate intelligence. What, then, set us on a divergent path from our closest cousins, the great apes?

Paying Attention

That was the question driving research from 1998 to 2017 in the Department of Developmental and Comparative Psychology of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. For nearly 20 years, the Max Planck team conducted controlled experiments comparing human children with chimpanzees and bonobos. A theoretical framework and interpretation of that work is now available from the team lead, Michael Tomasello, in the form of a book aptly titled Becoming Human.

To discover why humans differ, we must look not only at what we think separates us from the great apes, but when those differences emerge and how divergences in childhood set us onto a different path. To discover this, the researchers paid careful attention to stages in childhood development.

Even in the first year of life, unique human behaviors emerge. Infants only a few months old will engage in “protoconversations” with their caretakers. The caretaker, usually the mother, faces the infant and expresses some positive emotion, usually a combination of smiling and a happy vocalization. (Young infants can’t understand language but can reliably detect emotional tone.) The infant will listen, then “answer” with its own smile and vocalize. Then it will again wait for the caretaker. If the caretaker deviates from expectation, by waiting too long to reciprocate, or replying with a flat affect (e.g., “stone face”), the infant will often become upset.

It is important that these protoconversations are not primarily imperative in nature. They are distinct from the cries that signal specific unmet needs, such as an empty tummy or full diaper. Instead, the infants are creating emotional bonds with their caretakers. This process includes imitation but goes beyond mere mimicry. The infants are actively monitoring the adult’s emotional state and seeking to bring about emotional alignment. Apes do nothing like this. Tomasello theorizes that this is because of the different social contexts in which apes and humans rear children.

Apes are weaned at the age of 4 or 5. Until they have weaned their child, ape mothers will not become pregnant again. They cannot afford to. Among all the great ape species, mothers alone bear the burden of childrearing. The child will be in almost constant physical contact with the mother for all that time. Ape children and mothers do not engage in protoconversations.

In human societies, a single mother may give birth several times before children are even minimally independent. Consequently, caretaking is divided between the mother and others, such as the father or extended kin or social networks. In a situation where multiple adults are sharing care of multiple infants, it makes sense that infants learned to compete for adult attention. The innate mother-child bond isn’t enough to guarantee adequate care. Protoconversations may seem insignificant, but they actually kickstart capacities that will eventually lead to writing love poems and college admission essays, the summit of human culture.

At 9 months, infants reliably go through a developmental burst that takes them well beyond their great ape cousins. They begin to engage in “joint intentionality,” attending together with adults toward third-party objects. For instance, an adult might introduce a ball into the room and point at it. A 9-month old infant will understand not only that the adult is interested in the ball, but also that the adult wants the infant to attend to it. As the infant attends to the ball, it will keep tabs on the adult, continually monitoring the adult’s emotional state for signs that it is attending to the ball the way the adult desires. The interaction assumes a triadic structure—infant, adult, ball.

In other words, the infant constructs a frame of reference in which “we” are attending to the ball together. “We” are interested not only in the ball, but in each other, in how we feel about the ball, ensuring that we are on the same page. As in protoconversation, invitations to joint intentionality do not (necessarily) have any instrumental or imperative content. Later, of course, pointing could be a prelude to a specific command or request: “Bring that to me.” But at this stage, it’s merely the introduction to a shared experience.

Remarkably, great apes do not point to direct each other’s attention. They do have several attention-getting gestures, but almost all of them indicate specific demands: “Give me food,” “pick me up,” etc. Even apes taught a rich sign-language vocabulary, including labels for many objects, showed no interest in engaging in interactions with triadic structures. Apes certainly can discern what other beings are interested in, and even when other beings are trying to get their attention. But they are incapable of deriving information from that.

For instance, when chimpanzees are hunting for food hidden in barrels, a human experimenter will reach toward the correct barrel, trying to be helpful. The apes understand that the human is interested in the indicated barrel, but it doesn’t occur to them that her gesture has anything to do with their search. They ignore her and carry on, with one exception. If the experimenter has acted as though she is searching for food for herself, the apes will be very interested in her actions, trying to beat her to the food and secure it for themselves. To some extent, the apes have a “theory of mind,” the ability to model another being’s knowledge and intentions in order to predict its actions. But they are incapable of forming a triadic and recursive frame of reference, in which the experimenter and ape form a joint “we” that continually updates information and emotional state in reference to the search for food.

In contrast, young children are expert helpers. In one experiment, toddlers individually shared a play experience with a particular adult and a particular toy. Eventually, the toy was put somewhere that the toddler could see but the adult could not. When the adult re-entered the room later and started acting as though searching, the toddler intuited that the adult was searching for that toy. The toddler attracted the adult’s attention and pointed out the toy. It also works in reverse; toddlers will take adult direction on how to find a toy, provided an experience that has established a shared context. An impressive amount of recursive intentional thinking is already on display in this activity, so much so that it’s difficult to write it out explicitly: “I, toddler, know that you, adult, know that we know about the toy. You seem to me to want to find the toy, so I will point it out to you, trusting that you will interpret my pointing as indicating that I know your intentions and also know some relevant information that I wish to convey.”

Why do humans develop this way, when apes do not? Much of infant and early childhood play is structured in terms of role-reversal imitation. With very young infants, play is asymmetrical. The adult hides their face and then reveals it — peek-a-boo! The infant squeals in surprise. Or the adult tickles the infant’s arm. The infant laughs and flails. But a bit later on, the infant wants to join the game as an equal partner. They start to cover their eyes and vocalize, and they expect an appropriate response from the adult. They reach out to tickle back, and again expect to be greeted with laughter. The lesson of peek-a-boo or tickling is not that “you” do this to “me”, but rather that there is a “peek-a-boo-er” or “tickler” role, and a “laugh-er” role, and either of us may occupy that role at any given time. We are interchangeable within the structure of the game. This cognitive achievement opens the door for cultural learning.

But joint intentionality isn’t enough to get us out of our ancestral arboreal abodes and into high-rise apartment complexes. For that, one further capacity was necessary, which emerges in children around age 3. As young children begin interacting with peers, they use all the skills of joint intentionality so far developed. But they add on top of that “collective intentionality,” the perspective of the broader “we,” the group.

At age 3, children are able to think in generic terms—linguistically, socially, morally. These seemingly different dimensions of life are in fact intimately related. As Tomasello explains, “The two main ways that young children use generic language are in instructing others pedagogically in generalized cultural knowledge and in enforcing the norms of behavior formulated by the cultural group.”

An adult playfully says, “Look at my cute doggy” while holding up an octopus. “No, that’s not a doggy!” the children cry. “How do you know?” “Dogs have fur, and a tail, and floppy ears!” The child knows not only what a dog is like, but also what dogs are like. They also know that this knowledge is shared cultural knowledge, group knowledge, so it’s funny and silly when the adult pretends not to know.

Similarly, children are quick to inform other children when they appear to be doing something incorrectly: “That’s not where the ball goes. Put it in here, so it comes out there.” Or morally wrong: “We’re not supposed to yell,” the child yells (self-awareness develops later).

The basic skills of monitoring developed in infancy have generalized to the point that the child is now, at least rudimentarily, self-monitoring. They monitor how others, adults and peers, are viewing them in social situations and try to maintain favorable impressions. But more importantly, they’re building executive functioning, that is, pre-emptive self-monitoring based on previously internalized experiences. Not always successfully, of course. Impulse control problems lessen with age but never really go away (source: personal experience).

Executive functioning works only because the child has advanced to this higher level of collective intentionality, the view from the group, which can extend to an “objective” view, i.e., a view that doesn’t depend on any particular person’s perspective. There are conceptual differences between “Mommy says not to hit” (internalized joint perspective), “We don’t hit” (internalized collective perspective), and “It’s wrong to hit” (internalized universal perspective). Each stage of development grounds the next.

Helping Out

Many animals demonstrate remarkable pro-social behavior, including altruism and friendship. But human children are the animal kingdom’s apex helpers. As noted above, even infants are highly attuned to the emotional states of others and seek to bring about positive emotional alignment. We are all born guardians of the vibe.

Through role-swapping play children develop the capacity to imagine themselves in the shoes of others, and vice versa. That’s empathy. Adam Smith, the economist and moral philosopher, realized this in the eighteenth century, when he rooted fellow-feeling in “changing places in fancy with the sufferer.”1

There are three ways in which human children surpass the rest of the animal kingdom

First, at the outset of our lives, our helpfulness is mostly intrinsically motivated. Children will help without external direction or anticipated rewards such as praise, food, or stickers. But perhaps the reward they seek is a reputation boost or social bonding? No. Even in experiments where the “helpee” will not know that they have received help, and the children are aware that the helpee will not know, the children still offer help.

But maybe the children don’t really care about the people they help. Maybe they just like the good feeling that comes from providing help. That must be it; they’re just little egoists, basking in the glow of moral superiority. Well, one clever experiment measured children’s physiological reactions (pupil dilation, etc.) to someone being helped. It turns out that whether the child was the helper, or merely witnessed a third party provide help, they were equally pleased. It seems savior complexes are learned, not innate.

As a cautionary note for parents and economists, adults can undermine helpful behavior in children by encouraging it (subsidizing demand, as they say). If children are given external rewards such as stickers for helping (or any other intrinsically motivated behavior), when the external rewards are discontinued, the behavior will fall below baseline. The external rewards squelched the internal motivation.

Second, only humans are known to engage in paternalistic helping, that is, engaging in situations based on what we think will actually help, not necessarily based on what the other person wants. In one study comparing toddlers and chimpanzees, the experimenters set up a situation in which the study subjects knew that a particular tool was required to accomplish a task. An adult was trying to accomplish that task, but needed the study subject to retrieve the tool.

Now came the key intervention: the adult reached a hand out toward the wrong tool. (Chimpanzees can't understand pointing, but they can understand whole-hand reaching.) The chimpanzees reacted to the gesture and fetched the wrong tool. The human toddlers ignored the gesture and retrieved the correct tool.

This demonstrates that the toddler's motivation was to be helpful, not simply to obey or to please the adult. It also reinforces the larger claims made in Tomasello’s book. The toddlers can already distinguish to some degree between the objective ("what is helpful") and the subjective ("what this person wants me to do"). It also shows that even toddlers understand intentionality at a level chimpanzees don't. Chimpanzees understand human-want-thing, but toddlers are already chaining together layers of intentionality. What the adult really wants is to accomplish the task; the tool is just incidental. The adult is under a misperception, which the toddler ignores (or corrects) in the course of helping.

Third, children demonstrate what we might call temporally-extended empathy. If a child witnesses something unfortunate happen to someone (e.g., candy taken away), they are more likely to display preferential treatment toward that person later. This signifies a more advanced form of perspective-taking dependent on memory. The child reactivates the empathy felt earlier and acts on it in the present. This empathic balancing of the cosmic scales suggests a bridge to what may be a uniquely human concept: fairness.

It’s Only Fair

Fairness is interesting as a moral concept because it can be used both to enhance empathy, as when our instinct for fairness overcomes our selfishness, and to restrain it, as when we consider whether someone has proved worthy of help or resources. The experimental literature tracks the previous distinction between joint intentionality and collective intentionality. As infants develop their capacity to bond with a single other person in joint perspective, they become extremely willing to help. As children develop a collective or objective perspective, they start to question what kind of help is appropriate.

The way fairness expresses itself is culturally constructed, but in the earliest stages of psychological development, it expresses itself as the conviction that everyone of “us” deserves equality. But who is included in that “us”?

Experimenters look to differences in sharing behavior in different circumstances. For instance, have two young children enter a room through two different doors. Near the first door are three lollipops; near the second door only one. Sometimes the child blessed by “luck” will share, but not reliably. Now, take two children and have them work together at some task to earn a reward. Upon successful completion of the task, three lollipops fall out of a chute near one child, only one lollipop near the other. About 80% of the time, the better rewarded child will share. “We” worked on this together, so “we” deserve an equal share. Apes don’t share in these circumstances, presumably because they lack the capacity to engage in joint intentionality and form a “we”.

As children grow up, they start to enlarge their concept of “we” to include groups, sometimes in contrast to other groups. Collaboration remains a situation especially suffused with fairness thinking, but mere group membership can entitle someone to equal treatment. For instance, bringing treats to one’s classmates. In an experiment where one child was given treats to share with a play group, but the number of treats couldn’t be divided equally between all the members, the child often solved the problem by discreetly disposing of the extra treats in a trash can before entering the room. Equality over efficiency.

Of course, everyone getting equal of everything in all circumstances isn’t how human societies work. School-age children learn to modulate their sense of fairness according to cultural norms, and they start to punish “free riders,” who want to share rewards without collaborating.

The sticking point, unsurprisingly, is private property. Children are much less likely to share something they already think of as “mine” than future rewards or communal resources. Here we’re probably following the lead of our primate programming. Apes have strict dominance hierarchies that resolve who gets which food. If a higher-ranking ape and lower-ranking ape go for the same food at the same time, the lower-ranking one must break off the attempt. But once an ape has touched a piece of food, that food becomes theirs, and they won’t give it up without serious … persuasion. (An ape who gets a lot of food, such as an entire animal corpse or bunch of bananas, will give pieces of it away to placate harassers, but will keep the majority for themself.) It turns out that possession is nine-tenths of the law of evolution.

Fairness is only one example of human moral development. The broader point is that time converts our earliest instincts and capacities into norms that we internalize. My awareness of the judging other leads to my pre-emptive judgment on myself, and conscience is born. Tomasello has a beautiful summary of the developmental timeline:

From an early age, even before their first birthday, infants engage in processes of social evaluation. By three years of age children are making moral judgments: judgments that do not just express their personal preferences but assess how others meet the objective normative standars that “we” all share. By four or five years of age children discover that others are judging them in this same way, using the same normative standards, so they engage in active attempts at self-presentation to influence those judgments. But one cannot escape one’s own watchful eye, so children of this age also reverse roles and begin to evaluate themselves in the same way that they evaluate others, sometimes resulting in feelings of guilt for not acting in accordance with the shared standards. Six- and seven-year old children have begun to understand that they must make their own moral decisions—adjudicating between selfish motives, sympathetic motives, fairness motives, and conformity to various norms—and in so doing they begin to form their own social and moral identities. They make these moral decisions in ways that they can justify to others in the community and to themselves by giving reasons…. Internalizing the reason-giving process transforms social self-regulation into normative self-governance via one’s cooperative identity: “I now feel that I simply must do certain things in order to continue being the person that I am.”

From Social Groups to Culture

The sheer scale of human connectivity is staggering. Unlike most humans until recently, I don’t grow, hunt, or forage my own food. Every day I shovel into my mouth food acquired from other people, people I don’t even know. When I drive down the highway, I trust—very begrudgingly—that multitudes of strangers will follow the same rules I am, successfully enough that we won’t kill each other.

Great apes do not cooperate on a large scale. That’s not to say that they aren’t social. They certainly are. But the sociality of ape society depends on familiarity. The groups are small enough that every ape recognizes every other ape, not unlike the denizens of a pre-modern European village. 🎵There goes the baker with his tray like always… 🎵Apes are hostile to unfamiliar apes. They don’t do foreign diplomacy.

Humans expanded beyond kin groups by inventing culture. Culture is group identity based on shared norms and behavior. By age 3, children start to have cultural consciousness, the expectation that some knowledge, behavioral norms, and attitudes are shared broadly. They start taking certain things for granted. When someone, usually a peer, violates those expectations, they will try to explain and/or enforce them: “We don’t touch things on that desk.”

They also come to understand that there are, at least in principle, other groups of people who might do things other ways: speak other languages, wear other kinds of clothes, etc. Children do not necessarily pass moral judgment on difference, but they do express a preference for people who are similar to them. Homophily, “love of the same,” is the single most widely replicated result in social psychology.

Anthropologists explain this by referencing the unique situation of the Homo genus as it left behind its arboreal habitat for the wider world. We were obligate collaborative foragers, meaning trust was at a premium. But we were so successful at reproducing that we couldn’t keep track of every individual in the population. How could we signal to each other that we were good potential partners?

We conformed to group norms. We talked how others talked; we ate what others ate; we did what others did. Trust is based on predictability. I can trust you as a foraging partner because I think I know what you would do in various situations. You would do the same as me.

Perhaps this rubs you the wrong way, because you hold the modern liberal position that people of diverse backgrounds and beliefs coming together ultimately make for a stronger group. That position does not flow “naturally” from our evolutionary heritage. Instead, it is a recent historical invention. To maintain it, we may need to bridle our evolutionary instincts, exercising nurture over our nature.

Conclusion

In the 1970s, the biologist E. O. Wilson (and others) put the terms “sociobiology” and “evolutionary psychology” into public discourse. Since then, a growing number of intellectuals have been convinced that our best way of understanding human behavior in the present is by uncovering the origins of those behaviors in the deep past.

“Evo-psych” isn’t going away, but it’s not without its critics. There are two major obstacles to leveraging evolutionary biology. The first is that we simply don’t know that much about our evolutionary history. Huge swathes of our heritage lie in the realm of indirect evidence and conjecture. This is a content problem, which science is decently equipped to handle. Presumably, studies like Tomasello’s will yield more and better information over time. We can expect forthcoming answers to at least some of our questions as to why people are the way they are.

The second obstacle is less tractable. It’s philosophical. Even if we had extensive data at our fingertips, biological information doesn’t translate to ethical recommendations without subjective interpretation.

For instance, some people view our evolutionary past as a preferable state of nature. Civilization is a repressive and distorting artifice. The wellness industry taps into this narrative, inconsistently but incessantly. The “paleo” diet seeks to promote health by rescovering ancestral eating patterns, casting the agricultural revolution as a fall from Eden. My favorite book title from this group is Neanderthin: Eat Like a Caveman to Achieve a Lean, Strong, Healthy Body.

Some self-help gurus interpret evo-psych as providing unchangeable, fundamental truths of human nature. These need to be understood and embraced. Attempts to construct societies on other principles are ideological flights of fancy doomed to crash against the hard rock of reality. Jordan Peterson famously makes much of dominance hierarchies in nature. His “lessons from lobsters” select certain biological facts as interpretive keys to explain human social interaction. Of course, dominance hierarchies are central to great ape society, and it’s plausible that a good bit of human psychology is structured along the same lines. But Peterson latches onto them as the way things are, and leaps from there to the way things should be.

If I was inclined to play the same game, I might refute Peterson by referring to Tomasello’s study. Humans are not unique because they replicate primate dominance hierarchies, but because they alone engage in certain kinds of collaborative social interactions, structured by equality, reciprocity, and role-swapping. Large-scale society is possible because we can structure ourselves according to cultural norms that are not directly and straightforwardly selected by evolution.

In the end, I find it unlikely that evolutionary biology will replace philosophy and religion as the site of meaning-making. On the other hand, thinkers and spiritual seekers committed to meaning-making based on reality cannot afford to ignore its insights. This discipline is just another opportunity for self knowledge, which can (we hope) be catalyzed into wisdom through reflection.

https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/smith-the-theory-of-moral-sentiments-and-on-the-origins-of-languages-stewart-ed. Part First, Section 1, Chapter 1.