In 1942, the Nazis were carrying out the Final Solution, snatching up every Jew within reach. In September, they came for the Jews of Vienna, displacing them to the Theresienstadt ghetto, an overcrowded, underfed concentration camp that often served as a gateway to the still worse horrors awaiting at Auschwitz. Among the Viennese Jews herded into boxcars like cattle for the slaughter was Doctor Viktor Frankl, a psychotherapist.

On the day he and his family were taken, he was close to a personal breakthrough. For over a decade, his specialty had been suicide prevention. His youth counseling centers had reduced the teen suicide rate in Vienna to nearly zero. He had saved countless lives overseeing suicidal women at the Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital. After the Nazis took control of Austria and instituted regulations against Jewish professionals, he was forced into private practice in his parents’ home. But he had no intention of confining himself to a small, private arena. He had a message to share with the world.

In the 1940s, psychotherapy was dominated by the ideas of Freud and Adler. But based on his work with patients, Frankl became convinced that their schools were incomplete. They were insufficiently attentive to the human need for meaning. In addition to psychotherapy, aimed at remedying pathologies, people needed logotherapy, guidance toward living a meaningful life. He was working on a book that would explain his methods to the world. When his family was displaced, he hid the manuscript in his coat lining, hoping it would accompany him.

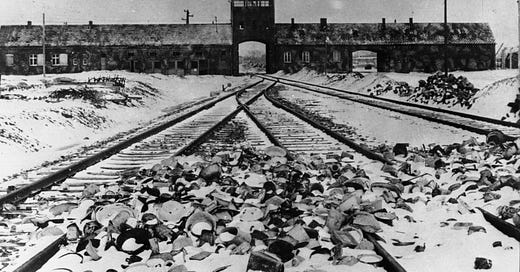

When the train pulled into Auschwitz, its stunned passengers shuffled forward into a hallway that forked to the left and right. A Nazi guard looked at each prisoner and gestured with his finger, this way or that. Left. Left. Left. Right. Left. Left. Frankl stood as straight as possible, trying to look young and healthy. The guard grabbed him by the shoulders, looked him up and down, then pointed right. The majority went left, to a “shower” that was in fact a lethal gas chamber. Their corpses were then collected and dumped into the great incinerators that spewed the victims’ ashes to heaven day and night.

On the right track, Frankl went to a real shower, where he was stripped of almost everything: his luggage, his watch, his overcoat, and his manuscript. Robbed of his identifying documents, he received a number. In a single hour, the concentration camp had taken this “someone” and made him into a “no one,” indistinguishable from anyone else.

Frankl spent the next two years in various concentration camps, bearing one indignity and injustice after another. At intervals, a quota of prisoners would be rounded up and “transferred” elsewhere. They were not heard from again. Life revolved around not having one’s number on that list.

Even for those who avoided the list, death was never far away. Sickness, malnutrition, and exposure were enough to finish off many before they were called to the gas chambers or other technologies of execution. Only a small fraction of those who entered the camps came out alive after the war. So, how did Frankl make it out alive?

On the one hand, Frankl owed his survival largely to his status as a doctor. At one point, typhus had broken out in the camps. Frankl volunteered to care for the sick; his noble sacrifice impressed the supervisors, who (he believed) worked behind the scenes to keep him from being executed.

But Frankl believed there was more to his survival than blind luck and the relative goodwill of the camp overseers. A psychological, or even spiritual element, kept him from relinquishing hope. Some prisoners committed suicide by running for the fences. Others simply laid down and died. He did neither, always believing that his survival was a worthwhile goal, that his life—difficult and impoverished as it was—meant something.

One sustaining force was his relationship with his wife. Sometimes she appeared to him and spoke with him. Not the real woman, of course. Frankl knew the image was a projection of his own mind. But it was a manifestation of his love for her. Concentrating on her, he was able to subsume the misery he was feeling in the joy of contemplating his beloved.

His other tether to the living world was his unfinished work. Late in the war, caring for typhus patients, he himself was stricken with sickness. He described his fight to stay alive and alert in the third person:

In a barrack in a concentration camp lay several dozen men down with typhus. All were delirious except one who made an effort to avert the nocturnal deliria by deliberately fighting back sleep at night. He profited by the excitement and mental stimulus induced by the fever, however, to reconstruct the unpublished manuscript of a scientific work he had written, which had been taken away from him in the concentration camp. In the course of sixteen feverish nights he had recovered the whole book—jotting down, in the dark, stenographic cue words on tiny scraps of paper.

Medical Ministry

Eventually, Allied forces liberated the camp, and Frankl returned home. Alone. His mother and brother had been sent to the gas chamber; his father and wife died from the horrific conditions of camp life. His broader community had been decimated. What was left?

There was the book he never wrote, a book that seemed all the more urgent after what he had experienced. The horrors of the war dashed the pre-existing beliefs of many survivors, but not Frankl’s. On the contrary, he felt that he had proven his philosophy through his own life. Not only had he survived, but he had maintained his essential hope in humanity and belief in the meaning and value of existence. He was entitled to preach what he himself had lived.

Frankl immediately set to work consolidating his experiences into useful lessons. In the year after his return, he delivered a series of lectures entitled “Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything.” Possibly never in the history of language has the word “everything” been used so euphemistically. Shortly after, in a nine-day writing frenzy, he finished the manuscript of his first and most famous book, which eventually received the title Man’s Search for Meaning. It was a memoir of life in the concentration camp, as well as a brief sketch of the psychological theory he had been developing.

Soon after, he finished the book that had been stolen from him in the camps. The English edition is titled The Doctor and the Soul, but that is a toothless translation of the original Ärztliche Seelsorge. The word Seelsorge literally means “soul-care” and is most commonly used to refer to the duty of Christian pastors to care for their flocks. A more accurate translation, then, might be Medical Ministry. Even though Frankl attempted to avoid stepping on toes, claiming that he was attempting only to supplement, not supplant, psychotherapy and religion, the title accurately indicates that the work is a provocative mixture of psychology, philosophy, and religion.

Frankl’s book was a critique of psychological theories, but he did so from a philosophical point of view. Indeed, the defects he found in Freud and Adler were symptomatic of a broader philosophical crisis, one that had spread throughout modernity and ultimately (he thought) caused the very terrors of the war:

The gas chambers of Auschwitz were the ultimate consequence of the theory that man is nothing but the product of heredity and environment—or, as the Nazi liked to say, of “Blood and Soil.” I am absolutely convinced that the gas chambers of Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Maidanek were ultimately prepared not in some Ministry or other in Berlin, but rather at the desks and in the lecture halls of nihilistic scientists and philosophers.

This is quite the combative statement, but Frankl worked hard to connect the dots. For him, the absolute most important philosophical concept, which also undergirds all psychological treatment, is the affirmation of each human being as a free and responsible individual.

Instead of immediately explaining what Frankl meant by that, it might be more illustrative to show the opposite. In the concentration camps, iron rationality and cold cruelty merged to produce an unprecedented horror. Nothing about life in the camps was normal. Everything was provisional. Much of Man’s Search for Meaning details the inmates’ abnormal psychology occasioned by their abnormal circumstances. And yet, Frankl also believed that the camps posed their victims with the same fundamental questions that ordinary life poses each human being.

Every detail of camp life was designed to degrade and dehumanize the prisoners. It robbed them of their personal identity (save a number), violated their humanity, and denied their agency.

The camp inmate was frightened of making decisions and of taking any strong initiative whatsoever. This was the result of a strong feeling that fate was one’s master, and that one must not try to influence it in any way but instead let it take its own course.

The inmate, already stripped of all visible uniqueness, was further encouraged to submerge himself in the mass of men around him, to be faceless, unnoticeable.

Just like sheep that crowd timidly into the center of a herd, each of us tried to get into the middle of our formations. That gave one a better chance of avoiding the blows of the guards who were marching on either side and to the front and rear of our column…. It was, therefore, in an attempt to save one’s own skin that one literally tried to submerge into the crowd. This was done automatically in the formations. But at other times it was a very conscious effort on our part—in conformity with one of the camp’s most imperative laws of self-preservation: Do not be conspicuous. We tried at all times to avoid attracting the attention of the SS.

Realistically, most people aren’t going to find themselves in concentration camps. So, there’s nothing to worry about, right? Unfortunately, no. Frankl saw trends in modern philosophy and psychology as leading us down the same track. In the 19th century, Nietzsche prophesied that the advance of science would not compensate for the death of God. He warned of a coming crisis, in which people, no longer given meaning by religion, would have to discover it for themselves. He feared most would not be up to the task. Frankl, in the middle of the twentieth century, called Nietzsche right on all counts (except, perhaps, on the tenacity of religion).

After all, what had science in the 19th and 20th centuries accomplished? Mostly, it had eroded human confidence. After Darwin, one had to argue rather than merely assume that humans were more than mere animals. Doctors sought the roots of human behavior in their biological makeup. Psychologists explained present experience as the result of childhood situations. Sociologists treated the individual as simple one data point in a group, interchangeable with the others.

Frankl was not anti-science. That was in fact the problem. The Darwinists had every right to interrogate human ancestry. The doctors were well within their bounds to correlate behavior with biological process. The sociologists performed a valuable service for society when they explained group behavior. And yet…

Even if all the other scientific disciplines studied human beings according to impersonal principles, at least the psychologists could be trusted to safeguard and champion the dignity of the human person, right? On principle, psychotherapy refused to admit that all human ills were physical in nature. One must examine the psyche, the soul, itself. But in fact, the major schools of psychotherapy had betrayed their mandate. They had become complicit in the scientific reduction of humanity.

Freud and Adler both sinned by reducing the personal, intentional, and free to the common, subconscious, and compulsive. That is, they were in the habit of explaining that the rational justifications you give for your behavior are not the real causes of your actions. Rather, formative events in your childhood—such as the kind of relationship you had with your mother or what order you occupy among your siblings—drive you. Hence the terms: sex drive, status drive, etc.

Frankl felt this kind of analysis as a betrayal he saw it as encouraging fatalism. Neurotics and depressives, he thought, were running away from agency. They were only too happy to hear an explanation of their condition that privileged other actors at work in the past. Science itself seemed to license their passivity in the face of their present condition. All that was the opposite of what they needed.

Our patient has a right to demand that the ideas he advances be treated on the philosophical level. In dealing with his arguments we must honestly enter into these problems and renounce the temptation to go outside them, to argue from premises drawn from biology or perhaps sociology. A philosophical question cannot be dealt with by turning the discussion toward the pathological roots from which the question stemmed, or by hinting at the morbid consequences of philosophical pondering. That is only evasion.

Logotherapy, or Existential Analysis

Although Frankl criticized psychotheraphy, he did not seek to replace it entirely. In his mind, it retained a place in the treatment of truly abnormal conditions: obsession, schizophrenia. In situations where people were beyond reason, a therapy of irrationality is called for. This corresponded well to the attitudes of most people at the time; therapy was for the sick, not for normal, healthy individuals.

Frankl, however, wanted to expand the realm of therapy. In his scheme, some people who thought they had psychological conditions, as well as many people who thought they were doing perfectly well, in fact met the criteria for receiving logotherapeutic assistance. Many people who are experiencing anxiety or depression are not, on his account, having an abnormal and therefore psychologically morbid reaction to human life. Rather, they are undergoing a normal reaction given their current relationship to matters of meaning and existence. They do not need to be cured of a disease; they need to be guided through their situation.

Existential health, the goal of logotherapy, is a matter of recognizing one’s inalienable freedom and responsibility. These two concepts are deeply intertwined, such that freedom serves as the logical ground of responsibility, but accepting responsibility is the only way to enact freedom.

At the heart of Frankl’s philosophy is a compatibilist doctrine of free will. No matter what restrictions—physical, mental, economic, political, historical—a person may live under, their fate or destiny, these are understood merely as constructing the racetrack on which one must compete. Each person is still free to determine how they will run the race.

The logotherapist, like a coach, equips the client with the motivation and skills necessary to run.

Our aim must be to help our patient to achieve the highest possible activation of his life, to lead him, so to speak, from the state of a “patiens’’ [recipient of action] to that of an “agens” [agent]. With this in view we must not only lead him to experience his existence as a constant effort to actualize values. We must also show him that the task he is responsible for is always a specific task.

Both freedom and responsibility are individual affairs, because each human life is unique. No person ever occupies the same space of possibility as any other. Although Frankl would not have used this illustration, we can draw an analogy with time travel. In Back to the Future, when Marty is sent back into the past, his bumbling around his hometown has unintendend consequences: the photo of his future self begins to disappear. From this he learns the lesson that his every move must be carefully considered, that any careless act could set history spinning on a completely different course. Most people buy into this “butterfly effect” view of time travel, that tiny changes can have enormous results. But all too often people fail to apply that same analysis to the present. In the present, they act as if even their largest actions will have little effect on the course of history.

In truth there is something about responsibility that resembles an abyss. The longer and the more profoundly we consider it, the more we become aware of its awful depths— until a kind of giddiness overcomes us. For as soon as we lend our minds to the essence of human responsibility, we cannot forbear to shudder; there is something fearful about man’s responsibility. But at the same time something glorious! It is fearful to know that at this moment we bear the responsibility for the next, that every decision from the smallest to the largest is a decision for all eternity, that at every moment we bring to reality—or miss—a possibility that exists only for the particular moment. Every moment holds thousands of possibilities, but we can choose only a single one of these; all the others we have condemned, damned to never-being—and that, too, for all eternity. But it is glorious to know that the future, our own and therewith the future of the things and people around us, is dependent—even if only to a tiny extent —upon our decision at any given moment. What we actualize by that decision, what we thereby bring into the world, is saved; we have conferred reality upon it and preserved it from passing.

The patients of logotherapy, and presumably most people, do not enter the doctor’s office with a clear sense of their unique humanity and the potentialities afforded by it. Hence the logotherapist’s task: to guide the patient “to find his way to his own proper task, to advance toward the uniqueness and singularity of his own meaning in life.”

Meaning exists where freedom and responsibility meet, where intentional action occurs for a committed cause. This merging gives rise to values. Meaning is the enactment of value. Frankl divides values into three types: creative, experiential, and attitudinal.

Creative values are those that we strive to bring about through action. By everyday activity, we attempt to make the world a little more the way it should be, or at least prevent its decline. At the very least, our actions are stamped with our character. Experiential values are realized through encounter. We meet with Beauty, or Truth, or Goodness, and we are transformed by it. These abstractions are encountered concretely in art or nature or other people. Lastly, attitudinal values include one’s disposition toward circumstances, one’s interior state even when one’s ability to change the external world is severely curtailed.

In keeping with these three sets of values, Frankl identified three principal arenas where meaning is found: love, work, and suffering. On the one hand, there’s a clear correlation between the three types of values and the three arenas: creative with work, experiential with love, and attitudinal with suffering. But it’s more interesting to look at the where the values interpenetrate the domains.

When Frankl talks about our need to find the mission of our life and realize our creative values in our work, it’s easy to mistake him for some kind of career guidance counselor. In fact, he is much less interested in what occupation we practice, more in how we practice it. We honor the uniqueness of our humanity not by crafting bespoke occupations but by letting our personality shine through in whatever work we have. He applied this line of thinking even to his own line of work, which was certainly tailored to his peculiar gifts and interests:

The meaning of the doctor’s work lies in what he does beyond his purely medical duties; it is what he brings to his work as a personality, as a human being, which gives the doctor his peculiar role…. Only when he goes beyond the limits of purely professional service, beyond the tricks of the trade, does he begin that truly personal work which alone is fulfilling.

We might be tempted to assume, then, that unemployment bars us from fulfilling our creative values. It is certainly a danger. Frankl discusses a condition called unemployment neurosis, in which the sufferer is reduced to apathy about their condition. Unemployment can be a swamp in which neuroses proliferate. All the same, though, creative values are not about making money per se, but (to paraphrase Frankl) about stocking our consciousness, our time, our lives with content. He points to volunteering, exercise, and socializing as ways to give shape to leisure time, but he also mentions things that fall under the purview of the experiential values: reading books, listening to lectures, appreciating art. When one type of value is frustrated, others can compensate.

Since Frankl was such a fierce opponent of collectivism, it’s not surprising that he rarely focused on the plights of the working class in capitalist societies. And yet, in his section on work, he called attention to subjective alienation as a feature of some jobs:

People’s natural relationship to their employment as the area for possible actualization of creative values and self-fulfillment often is distorted by prevailing conditions of work. There are, for example, those who complain that they work eight or more hours a day for an employer, and in his interest alone, doing nothing but add interminable columns of figures or stand at an assembly line and perform the same movement, pull the same lever on a matching—and the more that the job is reduced to impersonal and standardized movements, the more pleasing it is to the employer. In such circumstances, it is true, work can be conceived only as a mere means to an end, the end of earning money—that is, earning the necessary means for real life. In this case real life begins only with the person’s leisure time, and the meaning of that life consists in giving form to that leisure. To be sure, we must never forget that there are people whose work is of such exhausting quality that afterward they are good for nothing but falling into bed. The only form they can give to their leisure is to use it as a period for recovering their strength; they can do nothing more sensible with it than sleep.

With that, I leave the realm of work to consider briefly love as a realm of human values. For me, this is one of the weakest sections of the book, as Frankl is mostly concerned with conventional heterosexual romantic relationships. The field of love is, even on his account, much broader than romance. When he speaks generally about love, though, his core commitments to human dignity and uniqueness shine through.

Love is living the experience of another person in all his uniqueness and singularity…. In love the beloved person is comprehended in his very essence, as the unique and singular being that he is; he is comprehended as a Thou, and as such is taken into the self.

I find several things about Frankl’s view of love beautiful. First, it is based in reality. Whereas infatuation blinds, real love reveals. Yet love is not opposed to imagination. In fact, Frankl declares that the object of love is not simply the person, but the person in their idealized potential, the best possible version of that person. Love cultivates the other person towards that ideal through admiration. We realize our experiential values by affirming and basking in the goodness of our beloved. Moreover, love tends to vest the rest of the world with meaning and possibility, to “enchant” it. The presence of our beloved does not result in a monopolistic focus on each other; we can turn our gaze on the world and share in each other’s wonder.

No doubt Frankl is open here to charges of sentimentality and/or paternalism, and I would prefer him to flesh out his ideas in terms of other relationships, especially friendship. Nevertheless, I find his approach ennobling.

Finally, and most famously, in suffering we have the opportunity, or rather responsibility, to realize our attitudinal values. Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning is one of the best-known accounts of life in a Nazi concentration camp. The book is curious and unsettling, largely because the snippets of reported experience tend to be both heart-wrenching and inspiring, both terrible and (I am almost ashamed to admit) enjoyable to read. I do not think that was an accident.

The book, after all, is largely a first-person account. The central topic is not what concentration camp life was like, a thoroughly disheartening subject, but rather how Frankl himself responded to it. The book’s very existence removes in advance our greatest fear, that the protagonist will not survive. And make no mistake, Frankl is the protagonist, even the hero of his book. But his heroism has more in common with the sainted martyrs than with Hollywood.

Moments of creative and experiential values peek through at times. Even in the concentration camp, there were snatches of opportunity to make a positive difference or to appreciate beauty. But by far the dominant note is one of sheer resolve. Frankl made a promise to himself on the first day that he would not commit suicide, not even suicide by escape attempt. He couldn’t. He was conscious of a responsibility:

A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life.

Even in the absence of outward freedom, acknowledging responsibility gave him an inward liberation, the capacity to endure his circumstances and even make something out of them. There is a fine line to walk. Saying that suffering can result in good may end up trivializing wrong. But denying any potential goodness in the aftermath of suffering risks courting despair.

Perhaps Frankl’s most bracing claim is that suffering has meaning in itself. Psychological suffering—experiencing some state of affairs as painful, as wrong—is not pointless. Rather, it is the necessary consequence of having values. As soon as we stop finding a situation painful, we tacitly consent to its rightness.

Suffering has a meaning in itself. In suffering from something we move inwardly away from it, we establish a distance between our personality and this suffering. As long as we are still suffering from a condition that ought not to be, we remain in a state of tension between what actually is on the one hand and what ought to be on the other hand. And only while in this state of tension can we continue to envision the ideal.

Suffering can be fuel for change. Where change is impossible, it is at least a testimony that change is desirable. Therefore, our responsibility is not to eliminate our suffering, but to suffer well.

Freedom and Responsibility Before and After Frankl

Based on what’s already been said, it probably will not surprise you to hear that after the war, after the initial rush of memoirs and books, Frankl turned to philosophy. He earned a PhD in it, and his later works certainly focus on philosophical themes more than strictly medical or even psychological ones.

I see Frankl as rushing to fill the gap caused by the breakdown of religion in modern Western society. Up until about the 19th century, psychological and spiritual well-being was handled by one’s Jewish or Christian religious community. Local religious experts—priests, pastors, rabbis, elders—handled a stunning array of problems. Congregants came to them with straightforwardly theological and ethical questions, but also for general life advice, as well as for social commentary. Religion provided answers to question of meaning at every level: the whole cosmos, the religious community, and the individual. In this “sacred canopy,” the individual’s story is sensible because it’s nested within the broader stories of community and cosmos.

In this religious framework, humans are responsible to their divine creator and free either to cooperate with the creator’s will or not. As Frankl himself put it, “Life is a task. The religious man differs from the apparently irreligious man only by experiencing his existence not simply as a task, but as a mission. This means that he is also aware of the taskmaster, the source of his mission. For thousands of years that source has been called God.”

By the nineteenth century, though, Europe’s educated classes had become uneasy with traditional religion. The various wars and squabbles among factions, full of atrocious behavior on all sides, made it difficult to believe any tradition held the high ground. (See Lessing’s Nathan the Wise for this in parable form.) Biblical scholars and archaeologists had cast doubt on the Bible as a reliable narrative of historical events. Evolution emerged as an alternative creation story. Tightening networks of communication among intellectuals tended to erode identity barriers between Lutheran, Reformed, Catholic, etc. Enlightenment reason struck many as superior to faith for finding truth. The progress of the human race in this world seemed more exciting and attainable than a pilgrimage to heaven. Finally, the discipline of psychology offered a non-religious basis for treating the woes of the human soul.

Once philosophy, science, and psychology could be conducted without any explicit theistic or religious grounding, the role of religion in modern life shrunk. Some devout believers still turned to clergy and tradition for advice in all areas of life, a tendency we can loosely call fundamentalism. Most believers retained religion only for faith and (perhaps) morals, preferring to inquire about the rest of reality from various subject matter experts. Frankl himself participated in this: “the goal of psychotherapy is to heal the soul, to make it healthy; the aim of religion is something essentially different—to save the soul.” His medical ministry thereby claimed a large chunk of what was originally meant by Seelsorge (soul-care).

The problem for Frankl—or rather, Frankl’s patients—is retaining a sense of freedom and responsibility even when the traditional grounds for freedom and responsibility have been undermined. Frankl himself was friendly to religion, and, as is clear from his later work, had some idiosyncratic theistic beliefs himself. From his youth, he seems to have possessed a sense of personal freedom and responsibility quite naturally, maybe due to his personal temperament. As far as I can tell, he never struggled with these questions the way many of his patients must have, the way I do, perhaps the way you do, reader.

In the absence of obligation to God, Frankl wished to insert obligation to oneself, to one’s conscience. The task of life is not (necessarily) living up to God’s commandments, but living out one’s values. This aspect of Frankl’s philosophy has taken root in other psychotherapeutic approaches. In the 1980s, Steven Hayes made the identification and pursuit of realizing one’s values central to his Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, currently a popular variant of cognitive behavioral therapy.

Frankl, probably trying to avoid trampling entirely over religion, was adamant that the therapist should help the individual to discover and realize their own values. He always maintained that it was inappropriate for the therapist to serve as priest or guru, instilling their own personal values in the patient.

One wonders, though, what limits there are to this. Surely, in one sense, the Nazis were realizing their values by putting Frankl in a concentration camp. This is an extreme example, and I don’t think it seriously defeats Frankl’s approach, but it raises questions about the institutional divide that modern psychology has erected between personal values and morals.

Freedom, too, has struggled in the era after religious tradition. In the old days, it was enough simply to assert that people had free will. In both pagan and monotheistic cosmologies, freedom from causal determinism is a divine prerogative. Humans possess it because they carry a spark of the divine. This story perhaps hand-waves away some difficult questions, but subjectively it gets the job done.

Absent divine intervention, it’s not clear exactly what free will means. Frankl himself, too cultured to deny science, was uncomfortable with its direction and implications. He had reason to worry. One of the best-selling non-fiction books of 2023 was Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will by Robert Sapolsky. Sapolsky’s biography is almost a specter of Frankl’s fears. Raised as an Orthodox Jew but precociously interested in science, as an adolescent he abandoned all religious belief and dedicated himself to a life of research. He has spent decades fiddling with great ape brains, charting correlations between biological markers and behavioral outcomes. His thesis is that human behavior is just like great ape behavior, a mix of biological and environmental inputs that leads to determined outputs.

Now, Sapolsky isn’t necessarily correct. Quite a few philosophers and scientists disagree with him. But Sapolsky does create two challenges for Frankl. First, he discredits Frankl’s simple correlation between personal free will and social programs characterized by freedom from coercion. Earlier, I cited Frankl’s suspicion that nihilist philosophies ultimately led to the Holocaust. But Sapolsky’s politics are liberal and egalitarian, probably farther from Nazism than the average American’s. So, the link between believing in free will and believing in a free society isn’t as straightforward as Frankl imagined.

But more generally, Sapolsky indicates the constant challenge of science to Frankl’s existential philosophy. Science is necessarily from a third-person perspective. It explains things by reference to what is observable and testable. Insofar as science gains ground in society, the existential first-person perspective may lose out.

In the twenty-first century, our largest philosophical problem is how to reconcile third-person or scientific accounts of reality with our first-person experience of it. If Sapolsky says that our first-person feelings about freedom and responsibility are illusory and misguided, Frankl insists that they are the key to our psychological health. We are matter, and yet, we pursue meaning.

If reading this has made you curious about what science can say about human uniqueness, consider the article below, a summary of 20 years of primate research from the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology.

If you prefer a more poetic contemplation on nature as grace, as extravagant excess, join Annie Dillard on the banks of Tinker Creek.