Mountains, valleys, and rivers possess a great and mysterious power: they can make an ordinary person into an extraordinary author. The Renaissance poet Petrarch blossomed by the side of the Sorgue river in his beloved Vaucluse, “Enclosed Valley.” John Muir came into his powers during his wild, nearly solitary months watching the Yosemite Falls plunge into the Merced below. And in the 1970s, where the Blue Ridge Mountains made space for the Roanoke Valley, Tinker Creek was working its transformation on one woman who had started to record her daily walks around it in her journal.

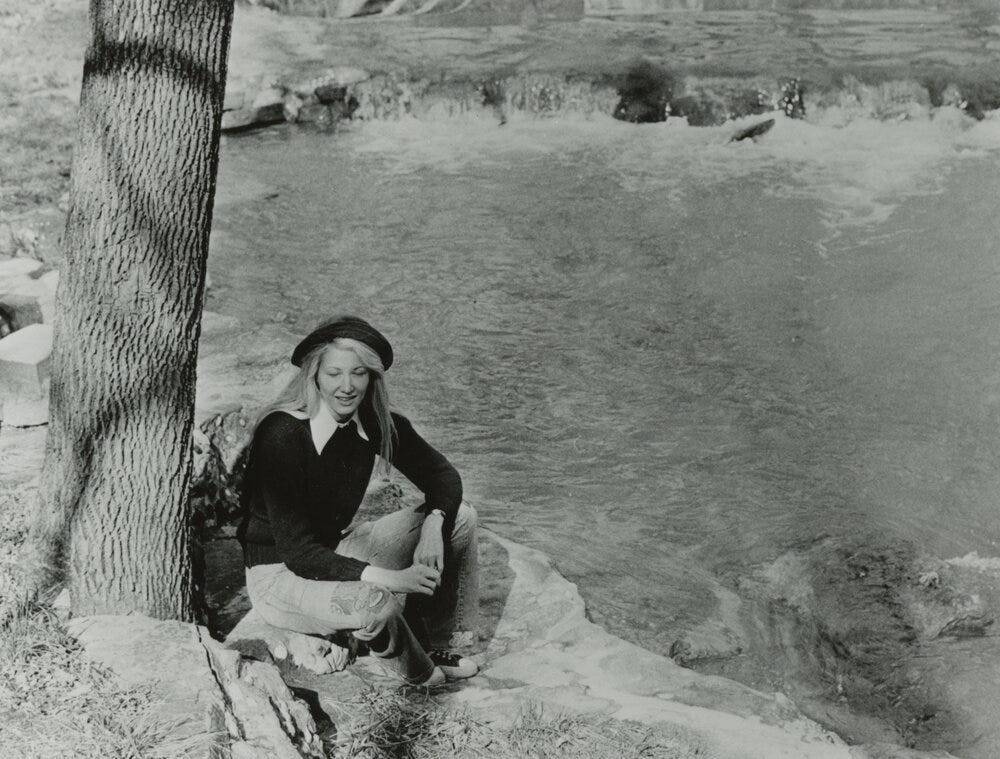

Annie Dillard was an aspiring writer, fresh off a Master’s thesis on Henry David Thoreau. Taking Walden Pond as a model for life, she lived in a simple farmhouse by the side of Tinker Creek, thinking and writing and taking walks. At first she concentrated on poetry, her focus in college, but over time all the thinking and walking and writing became intertwined. Her journal became a source of reflection, then the kernel of a work intended to explore the relationships between humanity, nature, and the divine.

It’s a good place to live; there’s a lot to think about. The creeks—Tinker’s and Carvin’s—are an active mystery, fresh every minute. Theirs is the mystery of the continuous creation and all that providence implies: the uncertainty of vision, the horror of the fixed, the dissolution of the present, the intricacy of beauty, the pressure of fecundity, the elusiveness of the free, and the flawed nature of perfection.

Attention, reflection, and time are the components of this alchemy, transmuting mere events into meaningful happenings. Every moment is a possible epiphany, which could reach up to heaven or down to hell, maybe both. To give an example, Dillard recalls a summer day when she was walking along the creek’s edge to scare the frogs and watch them jump. But one didn’t jump.

He didn’t jump; I crept closer. At last I knelt on the island’s winter killed grass, lost, dumbstruck, staring at the frog in the creek just four feet away. He was a very small frog with wide, dull eyes. And just as I looked at him, he slowly crumpled and began to sag. The spirit vanished from his eyes as if snuffed. His skin emptied and drooped; his very skull seemed to collapse and settle like a kicked tent. He was shrinking before my eyes like a deflating football. I watched the taut, glistening skin on his shoulders ruck, and rumple, and fall. Soon, part of his skin, formless as a pricked balloon, lay in floating folds like bright scum on top of the water: it was a monstrous and terrifying thing.

The first question, upon experiencing the strange and unsettling sight, is what happened. To this, Dillard can offer an explanation. A creature aptly named the “giant water bug” feeds by seizing and biting its prey. It secretes a poison that liquefies its victim’s insides, which it then sucks out. What Dillard saw was the aftermath of a recent hit-and-run.

But beyond the question of what happened is the question of why things are the way they are. She was having a lovely day, enjoying all the beautiful nature all around her. But then nature slaps her in the face; sometimes nature is getting your insides liquefied and sucked out. Is this all some kind of a sick joke? Dillard voices her doubts by quoting the Qur’an: “The heaven and earth and all in between, thinkest thou I made them in jest?”1

Dillard admits that there is no obvious meaning to be found in the universe, nothing that could easily be read off the face of things. But she does not give up the search.

Pascal uses a nice term to describe the notion of the creator’s, once having called forth the universe, turning his back to it: Deus Absconditus. Is this what we think happened? Was the sense of it there, and God absconded with it, ate it, like a wolf who disappears round the edge of the house with the Thinksgiving turkey? “God is subtle,” Einstein said, “but not malicious.” Again, Einstein said that “nature conceals her mystery by means of her essential grandeur, not by her cunning.” It could be that God has not absconded but spread, as our vision and understanding of the universe have spread, to a fabric of spirit and sense so grand that we can only feel blindly of its helm.

If there is a divine presence spread ever so finely across the face of creation, the one truly blasphemous act would be to refuse to look. Sentimental naturalism and cynicism are mirrored heresies, each creating a narrative of reality by ignoring the pieces that refuse to fit. Death and life, pain and wonder, join hands and dance.

Cruelty is a mystery, and the waste of pain. But if we describe a world to compass these things, a world that is a long, brute game, then we bump up against another mystery: the inrush of power and light, the canary that sings on the skull. Unless all ages and races of men have been deluded by the same mass hypnotist (who?), there seems to be such a thing as beauty, a grace wholly gratuitous.

Dillard provides examples: a mockingbird diving toward the earth, then at the last second exploding into glorious flight; sharks illuminated in the waves of the Atlantic. Why do these performances of beauty and grace affect us so? Why are we not as indifferent to nature as it often is to us? “If these tremendous events are random combinations of matter run amok, the yield of millions of monkeys at millions of typewriters, then what is it in us, hammered out of those same typewriters, that they ignite? We don’t know.”

It may not be possible to adjudicate the goodness of creation. There is no simple deductive argument leading from the way things are to a loving providence, though there perhaps remains a hint and a hope. If nature insists on anything, it is its own performative excess.

At the time of Lewis and Clark, setting the prairies on fire was a well-known signal that meant, “Come down to the water.” It was an extravagant gesture, but we can’t do less. If the landscape reveals one certainty, it is that the extravagant gesture is the very stuff of creation. After the one extravagant gesture of creation in the first place, the universe has continued to deal exclusively in extravagances, flinging intricacies and colossi down aeons of emptiness, heaping profusions on profligacies with ever-fresh vigor. The whole show has been on fire from the word go. I come down to the water to cool my eyes. But everywhere I look I see fire; that which isn’t flint is tinder, and the whole world sparks and flames.

What is one to do, then, in this world of ambiguous meaning but unambiguous display? “The answer must be, I think, that beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

As you leave Tinker Creek, learn how Yosemite Valley made John Muir into America’s foremost lover of nature.

Or voyage with Charles Darwin, discovering how his patient, loving attention prepared him for scientific success.

Surah Al Anbiya 21: 16. The Quranic verse is not phrased as a question, but Allah’s insistence on this point implies that people were entertaining the contrary.

Love this clear-eyed look about nature. What a terrible, wondrous moment with the frog. Enjoyed this exploration very much, Charles, thank you :)