People are made of carbon, of cells and organs, coursing blood and sparking nerves. But that is just the flesh. The spirit of a person is made of stories.

Some of those stories are told to us, some we infer from our surroundings, and some we write on our own. Or, as Jeanette Winterson put it:

It took me a long time to realise that there are two kinds of writing; the one you write and the one that writes you. The one that writes you is dangerous. You go where you don’t want to go. You look where you don’t want to look.

Today I’m exploring Winterson’s story. Or, better put, stories. Her first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985), was semi-autobiographical. She wrote about a girl named Jeanette who grew up in a home much like hers, in a family much like hers, in a church much like hers, and who went through first an awakening and then a tragedy much like hers.

The short version is that in 1960, infant Jeanette was adopted into a working-class family living in an industrial town outside Manchester, UK. Home was dominated by her emotionally unstable mother, whose extreme religiosity was part symptom of, part coping mechanism for, untreated mental illness. Jeanette’s family were members of a Pentecostal church that mandated strict behavioral guidelines to separate the holy from outsiders. They were strongly evangelical and charismatic, employing miraculous healings and exorcisms in their revival crusades.

Jeanette was raised to become a missionary, and even as a young teen showed promise as a preacher and evangelist. But when she fell in love with another girl in her church, one of her converts, the church would not accept her sexuality. After she refused to submit to an exorcism, she lost everything: her family, her church, her hometown.

The novel was successful far beyond her expectations. It made its way onto school reading lists in the UK, and in 1990 was adapted into a BBC television drama. The success of her story in turn raised questions. What did it mean for the novel to be semi-autobiographical? What was real and what wasn’t? What motivated her to write about herself in a partially fictional way?

In 2011, Winterson released a memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? This was partly to set the story straight, but moreso because she had quite a lot to say about the role of narrative in life. We are always living according to a story, a story that we co-create with our society. In childhood, some of us are handed a story we can live with. Or one that, with only a few adjustments, will suffice. Others of us find the story given to us in childhood so unworkable that it prompts a wholesale act of self-authoring. This is how Winterson puts it.

"I can't remember a time when I wasn't setting my story against hers. It was my survival from the very beginning."

"It's why I am a writer—I don't say 'decided' to be, or 'became'. It was not an act of will or even a conscious choice. To avoid the narrow mesh of Mrs Winterson's story I had to be able to tell my own. Part fact part fiction is what life is. And it is always a cover story. I wrote my way out."

In the rest of this article, I’m going to retell the basic story of Oranges, accentuating the parts I find most relevant to self-authoring. Then at the end we’ll return to the question of what it means to write our own stories.

To avoid confusion, I’ll be using “Jeanette” to refer to both the fictionalized and real versions of young Jeanette Winterson, “Winterson” to refer to the adult Jeanette Winterson as author of these books, and “Mrs. Winterson” to refer to both the fictionalized and real versions of Winterson’s mother.

Jeanette’s Story

Mrs. Winterson was lonely, eccentric, and very, very religious. Despite holding some idiosyncratic beliefs, she had fallen in with a form of fundamentalist, revivalist Pentecostalism. She felt trapped in her little life in Accrington, a poor industrial town 20 miles north of Manchester, England. But through radio, letters, pamphlets, and big tent evangelistic crusades, she joined the great evangelical missionary movement. If she couldn’t go herself into the hot and heathen reaches of the world, perhaps she could send someone else.

My mother, out walking that night, dreamed a dream and sustained it in daylight. She would get a child, train it, build it, dedicate it to the Lord:

a missionary child,

a servant of God,

a blessing.

So, Jeanette was adopted. It was made clear to her, early and often, that the adoption had been an act of religious devotion, that it entailed obligations. In a more neutral moment, Jeanette says, “I cannot recall a time when I did not know that I was special.”

By special she meant responsible for the fate of the world. Jeanette recalls a time her mother walked her up a nearby hill to look out over Accrington.

We stood on the hill and my mother said, ‘This world is full of sin.’

We stood on the hill and my mother said, ‘You can change the world.’

Most of the positive attention and quality bonding time Jeanette received at home revolved around her religious training. Mother, father, and daughter shared one bedroom. Every night Mrs Winterson would read the Bible as a bedtime story. She read straight through, Genesis to Revelation. A short break, then repeat.

She taught Jeanette to read from the Book of Deuteronomy. There were lots of animals in it to hold a child’s attention. She quizzed Jeanette about the Bible incessantly. Together they read reports of missionary activity around the world.

But there was a problem. Apart from her dream of raising a child as an offering to the Lord, Mrs Winterson had neither the capacity nor the desire to be a mother. Her father, who Jeanette tellingly often refers to as “Mrs Winterson’s husband,” was largely absent and wholly dominated by his wife.

During the sixteen years that I lived at home, my father was on shift work at the factory, or he was at church. That was his pattern.

My mother was awake all night and depressed all day. That was her pattern.

I was at school, at church, out in the hills, or reading in secret. That was my pattern.

Jeanette was a child with behavioral problems. Mrs Winterson’s behavioral solutions included locking her in a coal chute for hours at a time, locking her out of the house overnight, and instructing her husband in the art of administering corporal punishment.

Apart from instruction and punishment, Jeanette was largely neglected. Mrs Winterson was far more invested in the missionary movement and the church’s evangelization efforts. Neglect coupled with a rather extreme view of the supernatural led to at least one negative situation:

Once I went deaf for three months with my adenoids: no one noticed that either…. I had assumed myself to be in a state of rapture, not uncommon in our church, and later I discovered my mother had assumed the same. When [Aunt] May had asked why I wasn’t answering anybody, my mother had said, ‘It’s the Lord.’

Only when another church member noticed the problem and personally intervened did Jeanette receive the medical care she needed. Throughout the ordeal, which included a surgery and a hospital stay, her mother downplayed the seriousness of the situation. She was present only intermittently, always running off on important business for the Lord.

Some of Jeanette’s behavioral problems at school may have stemmed from the fact that she was different from other children. She had been raised with a different set of values and an idiosyncratic religious vocabulary. Worse, her mother and her church community actively worked to keep outsiders at arms’ length. They called outsiders unclean and unholy. Her mother referred to school as “the breeding ground.” Jeanette was put into school late and against her mother’s wishes; it took the threat of state action to get her into the classroom.

In school it was clear that Jeanette’s life revolved around religion far more than her classmates’ did. An assignment to give a presentation on your summer vacation was a disaster. The others all talked about their boring, run-of-the-mill family trips to the beach. Jeanette talked about church camp, where there were miracles and exorcisms. She too went to the beach, but to help with an evangelistic crusade, healing the sick and saving the damned. Similarly, for a cross-stitch assignment, she picked one of her church’s favorite Bible verses, “THE SUMMER IS ENDED AND WE ARE NOT YET SAVED”. She painted pictures of the Apocalypse, frightening the other children. She told them they were going to Hell.

Home and school were difficult places for Jeanette, but she had a third. Church was a place where she understood the culture, and it provided a buffer between her and her family. Or at least, by throwing herself into church, it pacified her mother, who was most tractable when it appeared things were working out according to God’s plan. For the people of her congregation, church wasn’t a Sunday morning affair, but an almost daily set of gatherings. Since church members constituted almost the entirety of the Wintersons’ social circle, church was the default background against which other activities intruded. In her memoir, Winterson recalled the demanding weekly schedule:

Monday night – Sisterhood

Tuesday night – Bible Study

Wednesday night – Prayer Meeting

Thursday night – Brotherhood/Black and Decker

Friday night – Youth Group

Saturday night – Revival Meeting (away)

Sunday – All day

In her novel, church is often played for laughs. The visiting evangelists are always saying goofy things, everyone is a bit odd as they’re swept up in the Spirit, Jeanette herself is always getting herself into an awkward situation. But in her memoir, Winterson allows herself to be wistful, to indulge the memory of what church meant to her.

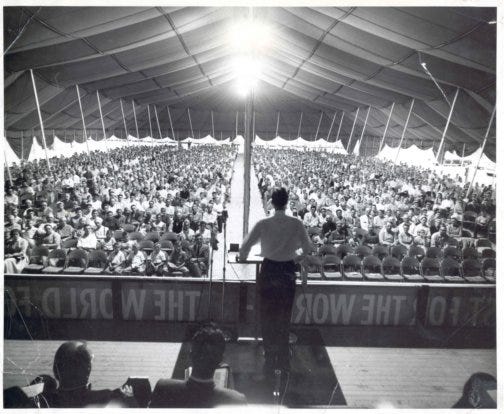

The Saturday night revival meeting was the highlight of her week. It was usually out of town, which meant there was a trip to look forward to. Ordinarily, they did not travel much. It was also a whole day affair. They went early, canvassing the area, handing out pamphlets and inviting people to come to the big tent for the evening service. Before the service, some church members would sit out by the street or on the beach singing worship songs, each contributing on whatever instrument they might happen to have.

The big tent crackled with excitement, its threshold drawing people together, at least for a time.

If you want to save souls – and who doesn’t? – then a tent seems to be the best kind of temporary structure. It is a metaphor for this provisional life of ours – without foundations and likely to blow over. It is a romance with the elements. The wind blows, the tent billows, who here feels lost and alone? Answer – all of us. The harmonium plays ‘What A Friend We Have in Jesus’.

In a tent you feel sympathy with the others even when you don’t know them. The fact of being in a tent together is a kind of bond, and when you see smiling faces and when you smell the soup, and the person next to you asks your name, then quite likely you will want to be saved. The smell of Jesus is a good one.

The tent was like the war had been for all the people of my parents’ age. Not real life, but a time where ordinary rules didn’t apply. You could forget the bills and the bother. You had a common purpose.

But even regular Sunday church services were intended to have a similar evangelistic fervor, especially if a visiting preacher was in town. In Oranges, Jeanette had started developing feelings for a girl in town, Melanie. She didn’t know what these feelings were. She lacked the experience to feel them clearly and the vocabulary to delineate them. But she did what she had been trained to do; she invited Melanie to church.

I’d forgotten that Pastor Finch was visiting on his regional tour. He arrived in an old Bedford van with the terrified damned painted on one side and the heavenly host painted on the other. On the back doors and front bonnet he’d inscribed in green lettering, HEAVEN OR HELL? IT’S YOUR CHOICE. He was very proud of the bus, and told of the many miracles worked inside and out. Inside had six seats, so that the choir could travel with him, leaving enough room for musical instruments and a large first-aid kit in case the demon combusted somebody.

As usual, Winterson describes the service comically, from Pastor Finch’s newly composed hymn You Don’t Need Spirits When You’ve Got the Spirit to his description of casting out demons across the English countryside. Winterson also plays up the incipient sexual tension between the girls, which Melanie appears more aware of than Jeanette. In fact, the narration suggests that that very awareness led Melanie to make a drastic decision. At the climax of the service, when sinners were invited to come to the Lord for salvation, Melanie responds. The entire church erupts in joy. Pastor Finch drives off with the Salvation Flag flying high over the van.

Their relationship developed in good Christian fashion, at first. As a new believer, Melanie needed a counselor to teach her the Bible and the ways of the holy, so Monday afternoons became prayer and Bible study at Melanie’s house. Jeanette and Melanie volunteered together at church events. Melanie wanted to study theology and be a missionary like Jeanette.

Eventually their relationship turned romantic and physical. Jeanette stumbled into it, not fully knowing what she was doing. After all, her entire sex education consisted of her mother saying, “Don’t let anyone touch you down there,” while gesturing vaguely to her midsection. Winterson describes the relationship with tenderness and discretion. I’ll skip past it to the next important point, how it ended.

One night Melanie was staying over at Jeanette’s house. In the middle of the night Mrs Winterson burst in with a flashlight, catching them sharing the same bed. She put the pieces together, but for a time, nothing happened.

Rather than confront her daughter directly, Mrs Winterson enlisted the church. In Oranges, the confrontation occurred during the church service. The pastor announced from the pulpit that the two girls had fallen under Satan’s spell, that they were full of demons, that they had been corrupted by unnatural passions. He called on them to renounce their love and repent of their sin.

He turned to Melanie.

‘Do you promise to give up this sin and beg the Lord to forgive you?’

‘Yes.’ She was trembling uncontrollably. I hardly heard what she said.

‘Then go into the vestry with Mrs White and the elders will come and pray for you. It’s not too late for those who truly repent.’

He turned to me.

‘I love her.’

‘Then you do not love the Lord.’

‘Yes, I love both of them.’

‘You cannot.’

That wasn’t the end of the matter. The elders of the church came to her home the next morning and stayed until late in the evening, praying over her and rebuking the demons. When she refused to repent, her mother locked her in the parlor for two days without food. Then the elders came back and began again. (In her memoir, Winterson says that one of the elders beat her and sexually assaulted her, a detail so dark that she omitted it from Oranges.) Imprisoned, starved, and badgered beyond endurance, Jeanette announced that she would repent, just to get them to leave.

For a time, everyone pretended everything was back to normal. Melanie went away to stay with some relatives, and Jeanette even resumed her preaching and evangelizing. But there is a limit to how much mistreatment a person can take, even if it is given in the guise of helping. Betrayed by her lover, abused by her mother, targeted by her church, Jeanette had crossed a threshold.

Eventually there was another girl, another discovery, another confrontation. This time the church was less willing to forgive, and Jeanette was less willing to repent. They went their separate ways, in that Jeanette was no longer welcome at home or at church, and she didn’t really care to be.

Writing Our Own Story

Jeanette, both fictional and real, left for London and eventually made her way to Oxford, where she read English Literature. With that training, she wrote Oranges. In one respect, I have been quite negligent in my description of the novel. I’ve done a decent enough job with the plot, but a significant portion of Oranges diverges from the primary narrative.

The first few chapters each end with a self-contained fantasy story, a little fairy tale or fable that shares themes with what’s happening to Jeanette. They are not introduced in any way, leaving it up to the reader to decide whether to treat them as inserts from the narrator or as creative daydreams from Jeanette.

As the novel progresses, these sections get longer and more complex. Some read like miniature essays, others like short stories. When Jeanette is under the greatest stress, the central narrative gets more vague, whereas the stories get more vivid. It is as if Jeanette is dissociating, coming to understand herself through these allegorical tales.

For instance, after her second relationship is discovered, the church leadership made her one last ultimatum. She must give up her church leadership duties, submit to another exorcism, and go away to a church-run guest house for extended spiritual recuperation. Jeanette told the pastor she would give her answer the next morning. Then this passage intervenes in the story. Are we to read it as a dream?

Sir Perceval has been in the wood for many days now. His armor is dull, his horse tired. The last food he ate was a bowl of bread and milk given to him by an old woman. Other knights have been this way, he can see their tracks, their despair, for one, even his bones. He has heard tell of a ruined chapel, or an old church, no one is sure, only sure that it lies disused and holy, far away from prying eyes. Perhaps there he will find it. Last night Sir Perceval dreamed of the Holy Grail borne on a shaft of sunlight moving towards him. He reached out crying but his hands were full of thorns and he was awake. Tonight, bitten and bruised, he dreams of Arthur’s court, where he was the darling, the favourite. He dreams of his hounds and his falcon, his stable and his faithful friends. His friends are dead now. Dead or dying. He dreams of Arthur sitting on a wide stone step, holding his head in his hands. Sir Perceval falls to his knees to clasp his lord, but his lord is a tree covered in ivy. He wakes, his face bright with tears.

These insertions, tantalizingly relevant and yet unexplained, elevate Oranges from a mere coming-of-age story into serious literature. Many of them feature grief, homesickness, and the thread by which the past continues to influence the present. In times of intense stress or depression, memory fails. We may be seeing Winterson stitching together the fragments of the past with her own fabrications.

But Winterson doesn’t think what she is doing is unique at all. We are all confabulators, all constantly writing and rewriting as we must in order to move forward. Fact and fiction intermingle. As another one of her insertions explains:

That is the way it is with stories; we make them what we will. It’s a way of explaining the universe while leaving the universe unexplained, it’s a way of keeping it all alive, not boxing it into time. Everyone who tells a story tells it differently, just to remind us that everybody sees it differently. Some people say there are true things to be found, some people say all kinds of things can be proved. I don’t believe them. The only thing for certain is how complicated it all is, like string full of knots.

Winterson is distrustful of single, authorized accounts of the past:

People like to separate storytelling which is not fact from history which is fact. They do this so that they know what to believe and what not to believe. This is very curious. How is it that no one will believe that the whale swallowed Jonah, when every day Jonah is swallowing the whale? I can see them now, stuffing down the fishiest of fish tales, and why? Because it is history. Knowing waht to believe had its advantages. It built an empire and kept people where they belonged, in the bright realm of the wallet…

So, true to her beliefs, she included sections of pure fiction in her semi-autobiographical tale. She acknowledges that not everything in the narrative portion of Oranges is how it actually happened. It was, as she said, “a cover story.” And yet, the presence of fictive elements doesn’t make it any less the story of her life:

I told my version—faithful and invented, accurate and misremembered, shuffled in time. I told myself as hero like any shipwreck story. It was a shipwreck, and me thrown on the coastline of humankind, and finding it not altogether human, and rarely kind.

Not all of us are equally conscious of the extent to which we are all authors of our own lives. Winterson had no choice but to take up the pen. Her family and church cast her as a hero, a missionary, a blessing for the Lord. But it also told her that she couldn’t fulfill that stories as she was. The opportunity to fulfill her story was taken from her. For her choice, she was cast as the rebel, unholy and unforgivable.

I needed words because unhappy families are conspiracies of silence. The one who breaks the silence is never forgiven. He or she has to learn to forgive him or herself.

One temptation of autobiography is abdication of responsibility. Things just happened to me. People just treated me a certain way. I played no role in how things played out. Early on in Oranges, Jeanette is mostly a passive character, but that is appropriate for a child. A child really does have very little agency in the course of their life. But toward the end, Jeanette accepts responsibility for her choices. In one sense, she is pushed out, but at the same time, she accepts that moving on is the right decision for her, the one that honors who she is and what she loves.

In my next article, I’ll return to Winterson, focusing on the difficulties of deconstruction. A person alienated from the subculture of their youth still bears the marks of their origins. As the Roman poet Horace said, “Those who flee across the sea change the sky but not their soul.” The past cannot simply be blotted out; the ties that bind are rarely cut clean. The past is never really past, but an ever-present concern.

For more on the necessity of embracing responsibility for one’s destiny, see this essay on Viktor Frankl’s classic Man’s Search for Meaning.

For a meditation on what we should expect from our religious communities, on the delicate balance between affirmation and challenge, see this piece on Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota series.

The quotable quote I want to always remember: "People are made of carbon, of cells and organs, coursing blood and sparking nerves. But that is just the flesh. The spirit of a person is made of stories."

I also loved the bit about how some of us are given stories we can live with, more or less, and others are given unworkable ones. Sometimes I think about what I would say if I had a child - what I'd like to have known earlier when I was a child - and that is that this whole business of Earth is just an absolute mystery, and none of us know with complete certainty what's going on.

Thanks for this post!