Understanding requires perspective; perspective requires distance. The biggest challenge we humans face in understanding ourselves is that we’re simply too close to the subject under investigation. We are trying to stand under the microscope while also looking through the eyepiece. Stymied, we turn to an indirect approach. We look around at the rest of the universe and try to make sense of our story in relation to that.

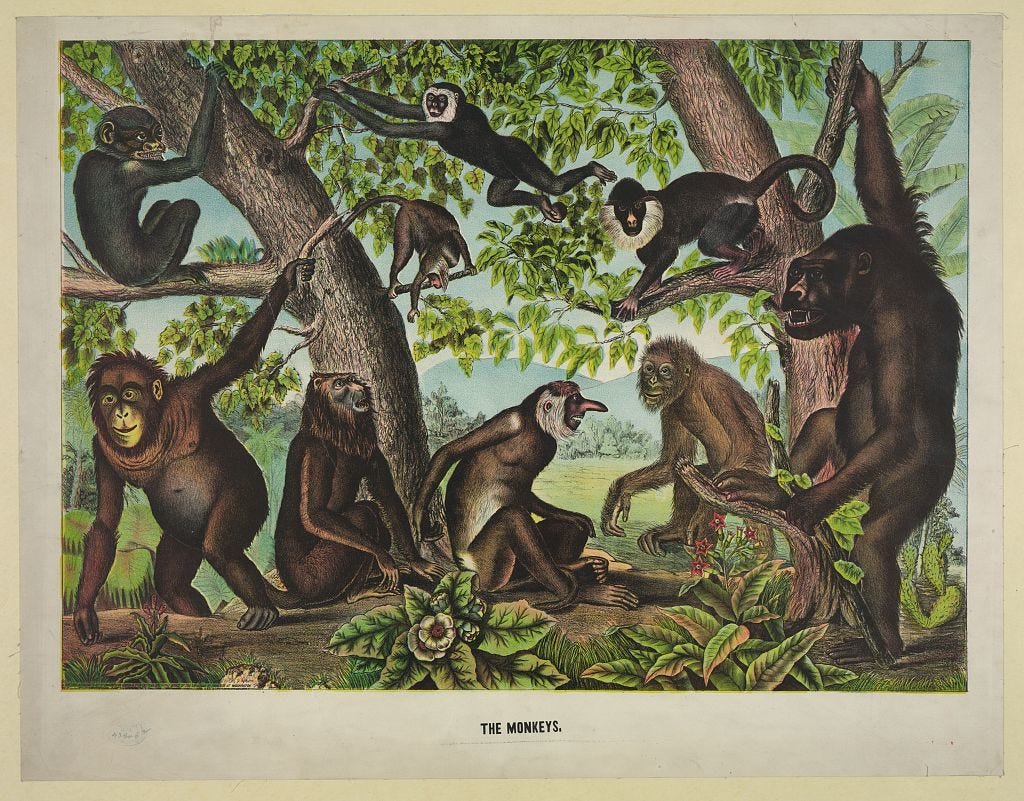

Traditionally, we turn to the animal kingdom. We can relate to it. These creatures hunt and sneak and squawk and pounce and store food and rear young. Many have eyes and faces, and we can’t shake the feeling that their expressions mean the same thing ours do, even when that can’t be. Can it?

Representing animals as human-like in an attempt to understand humanity better is an ancient practice. Aesop’s fables are full of wily foxes, cunning crows, greedy dogs, defenseless lambs. But the animal protagonists are transposed into human situations to illustrate human virtues and vices: “Don’t listen to flattery,” “Don’t trust people who promise to much,” “Learn from others’ mistakes.”

Similarly, individuals or even groups of people may form an affinity for specific animals. Totems from across the world portray animals important to particular clans or tribes. Animals were common in medieval heraldry, and even modern sports teams compete under the banner and colors of animals. By identifying an animal with a certain virtue and then identifying ourselves with that animal, as if through the principle of associativity, we come to possess that virtue.

My favorite exploration of the animal-human relationship in Carl Sandburg’s poem Wilderness. The first stanza reads:

There is a wolf in me . . . fangs pointed for tearing gashes . . . a red tongue for raw meat . . . and the hot lapping of blood—I keep this wolf because the wilderness gave it to me and the wilderness will not let it go.

The following stanzas acknowledge other animals—fox, hog, fish, baboon, eagle, mockingbird—that all live inside him. He understands himself as a zookeeper, a menagerie manager. And who doesn’t feel an eagle in them, yearning to soar free, or a hog, longing to stuff itself and laze in the sun?1

And yet, in the Christian West, there was a vague sense that this human-animal business is all a bit silly. Aesop’s fables were directed at children. The anthropomorphic animals in the margins of medieval manuscripts fluctuated between a game, moral messaging, and literary allusions. The conviction that God made humans unique, in God’s own image, on a separate day of creation raised a barrier between humanity and the rest of the natural world, one that rendered analogies playful and partial at best.

Nature Red In Tooth And Claw?

After Darwin’s Descent of Man, parallels between humans and animals became the business of serious scientists. After all, no sharp dividing line remained between humanity and the rest of the animal kingdom. We began to look at animals, especially primates, as distant cousins. Learning from them seemed less whimsical.

Here we encountered a problem. Nature can seem rather cruel and arbitrary, especially compared to the old picture of God lovingly creating each type of creature and tending to them all in perpetuity. It was Christian teaching until the modern era that species could not go extinct, because each species reflected God in a unique way, and God would not allow the world, the mirror of his glory, to be so defaced. But Victorians were aware of fossils of species no longer existing, and they could see the way industrialization was disrupting European biomes.

The most poignant expression of the distress caused by these realizations came from the pen of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His In Memoriam A.H.H. considered the implications of extinction.2 First, Alfred says, everything alive desires to live. He considered this a God-given impulse. Which raises the question:

Are God and Nature then at strife,

That Nature lends such evil dreams?

So careful of the type she seems,

So careless of the single life;

That is, prey and predator is the rule everywhere. The animal kingdom is an arena of fierce competition and death. Species persist, but only at immense loss of life. The realization of such suffering is enough to unsteady him: “I stretch lame hands of faith, and grope … And faintly trust the larger hope.” But worse is to come, because the extinction of species is a new level of dismay.

“So careful of the type?” but no.

From scarped cliff and quarried stone

She cries, “A thousand types are gone:

I care for nothing, all shall go.

What then of humanity, caught between faith in supernatural goodness, which seemed less justified by the day, and observations of the natural world, which seemed incapable of justifying anything?

Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law —

Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shriek’d against his creed —

Tennyson’s canto ends with a whimper, despairing of working out an answer in the present, hoping that one will be found “beyond the veil.” The main contribution of this poem was to put the phrase “nature red in tooth in claw” into the vernacular, a phrase most people probably don’t even associate with the poem. The central problem for Tennyson is that it seems impossible to derive our moral intuitions from nature.

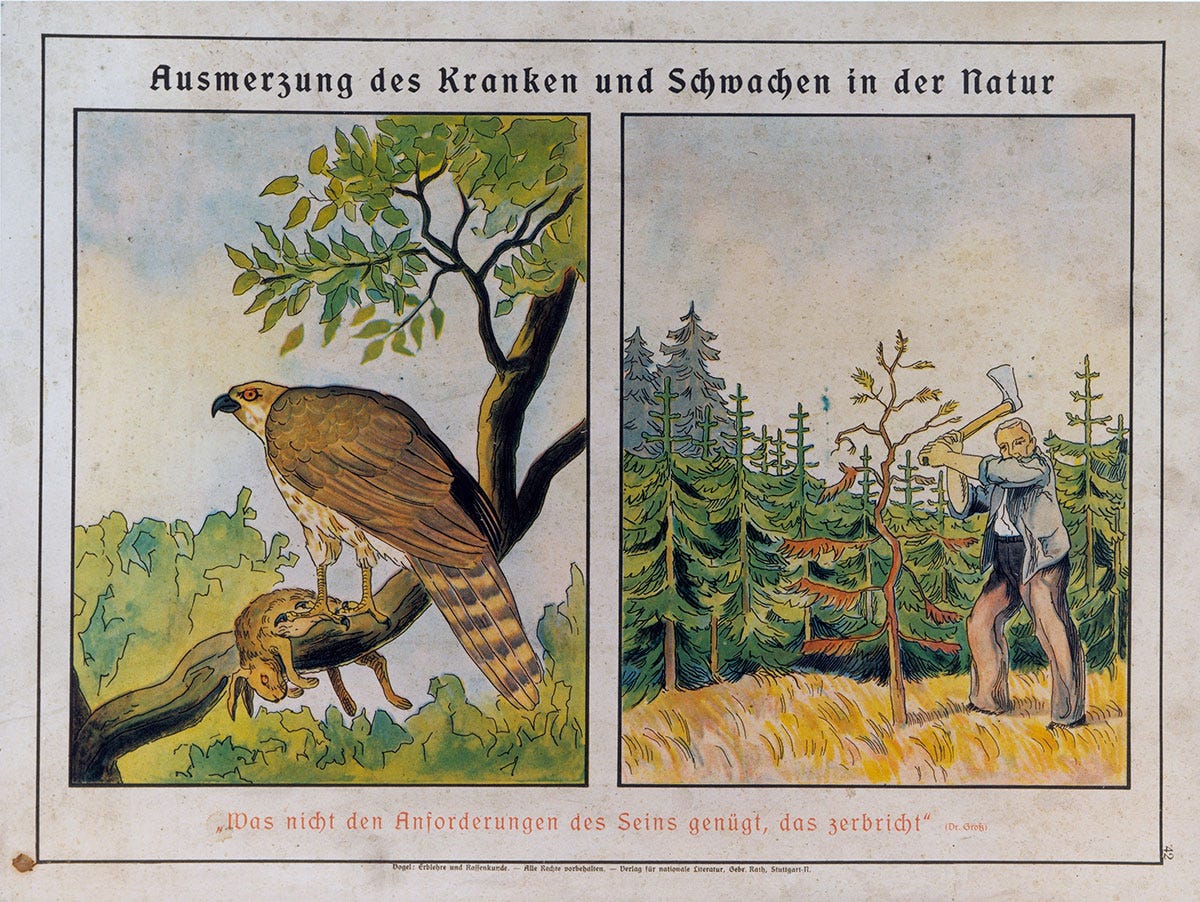

Unfortunately, Tennyson’s bleak description of nature became a moral principle among one group of people attempting to apply evolutionary thinking to human society: the Social Darwinists. They homed in on terms like “competition” and “scarcity,” building a philosophy that reaffirmed existing social hierarchies, in which they—conveniently—were already on top.

Of course, this is a partial and prejudiced look at the animal kingdom. The “circle of life” may require violence, but there is also plenty of collaboration and coexistence, if we are willing to look for it.

The Plants of the Earth Will Teach You

But just as we are too close to ourselves to get perspective on humanity, perhaps we’re too immersed in stories of animal violence to form new narratives. In that case, perhaps it’s worth turning our attention (pardon the pun) farther afield. Here we follow the recommendation of the Jewish wisdom text, The Book of Job:

But ask the animals, and they will teach you;

the birds of the air, and they will tell you;

ask the plants of the earth, and they will teach you;

and the fish of the sea will declare to you.

Plants are sufficiently distantly related to us to afford us the perspective we desire. The animal and plant kingdoms separated over a billion years ago. Our common ancestors were single cells that had welcomed mitochondria into their membranes. When the proto-plants suggested adding a chloroplast to spice things up, the proto-animals politely declined.

Plants may be very distant cousins, but they’re also intimately familiar. We evolved alongside them, using them for food and shelter. Of all the plants that have shared a long and complicated history with us, none shaped us more than trees.

The forest is the cradle of humanity. Many of the physical and mental adaptations that mark us as primates arose precisely to allow us to survive in an arboreal world. Our binocular vision, with both eyes pointing ahead, gave early hominins the ability to judge distance more accurately, allowing them to traverse the canopy.

Our fingers, terminating in pads and prints rather than squirrel claws or woodpecker talons, are superior at grasping and manipulating thin branches. Great apes are sufficiently dexterous and intelligent to build nests in the canopy, where they are safe from predators. Being able to sleep through the night started a virtuous cycle in which we were able to grow more intelligent.

Even our upright posture was probably developed for life in the trees. The heavier the primate, the less effective it is to cling to a single branch. Instead, they almost bounce across the branch beneath them while simultaneously reaching overhead for stabilization and weight diffusion.

Even when, some 20 million years ago, climate change nudged early Homo outside their forest homes to brave the African savanna, trees furnished them with the means to do so. Wooden sticks became the first digging tools, granting access to calorie-rich roots and tubers. Crude wooden shelters kept these apes warm as they became hairless. Fire kept predators away, and eventually transformed our jaws and digestive systems into the configuration we’re familiar with today.3

Trees are marvelous in terms of what they’ve done for humanity, but there is even more wonder to be found in observing them for their own sake.

Wisdom of the Wild Wood

1. It takes a forest

A powerful, lone oak towers over a flat field, casting its shade over lazy cattle fleeing the noonday sun. It’s a perfect pastoral picture, but it’s not the kind of environment most trees prefer. Oaks may have a solitary streak, but most trees flourish best packed tightly together with their own kind.

The fate of solitary trees is largely predetermined from the beginning. The seed falls either on favorable soil—moist but not soaked, deep, sufficiently loose—or unfavorable. These conditions determine how well the tree can extract nutrients from the soil, and in turn, how well it can grow and how long it can live.

Trees in forests play by different rules. First, they rig the game from the start. When enough trees gather close together, they form a microclimate. Many species will stretch their upper leaves, i.e., their crown, out until they almost touch, but no farther. This respect for one another’s space is called “crown-shyness.” To the human observer looking up, the trees seem to be creating a wild labyrinth of sky. The trees are limiting the amount of light that can reach the forest floor. By doing so, they keep the ground cool and moist, improving the overall quality of the soil.

The trees also pack in close together to ensure that biomass isn’t wasted. Leaves, even pine needles, take energy to grow. When they fall, they carpet the forest floor, and eventually are reduced to humus, that dark organic rich in moisture and nutrients. In all these ways, the forest is biasing the next generation for success.

2. Sharing is Caring

Forest collaboration goes beyond community service projects. Trees cooperate from top to bottom. Peter Wohlleben, in his classic The Hidden Life of Trees, describes how beeches use their root systems to enroll in “social security.”

Under the earth the beeches’ roots stretch toward each other, intending to intertwine. To accomplish this, they need some help from fungi in the soil. Every shovelful of forest soil is criss-crossed by miles of microscopic fungal filaments called hyphae. The trees’ fine roots, closer to the surface, physically interface with the hyphae. The fungi link the tree roots together into a larger network scientists have dubbed “the wood wide web.” Both nutrients and information can now be transmitted throughout the root system.

The goal of all this is to equalize production and redistribute wealth. Wohlleben relays the astonishing findings of a research institute in Aachen: “The trees synchronize their performance in undisturbed beech forests…. The rate of photosynthesis is the same for all the trees…. All members of the same species are using light to produce the same amount of sugar per leaf.”

This allows the trees to grow even closer together than appears prudent to human observers. Packed in tight, the young beeches support the elderly, the healthy the infirm. Rather than jostling their neighbors for space, they accept the limitations of the community. Wohlleben explains this counterintuitive behavior:

But isn’t that how evolution works? you ask. The survival of the fittest? Trees would just shake their heads—or rather their crowns. Their well-being depends on their community, and when the supposedly feeble trees disappear, the others lose as well. When that happens, the forest is no longer a single closed unity. Hot sun and swirling winds can now penetrate to the forest floor and disrupt the moist, cool climate. Even strong trees get sick a lot over the course of their lives. When this happens, they depend on their weaker neighbors for support. If they are no longer there, then all it takes is what would once have been a harmless insect attack to seal the fate even of giants.

Trees are so convinced of the value of this arrangement that they are willing to pay a premium to the fungi that enable it. Up to a third of a tree’s glucose production is offered as tribute. As high as this sounds, it’s still a good deal. After all, fungi perform several other useful functions, such as helping with decomposition and priming the trees’ defense mechanisms in anticipation of attack.

3. Alliance is the Best Defense

There is no hide and seek in the world of trees. Flight is not an option. This vulnerability has been unforgettably voiced by the folk music group Spell Songs in their song “Heartwood.” Karine Polwart personifies a tree entreating a lumberjack to leave it be: “Would you cut me to the heartwood, cutter?” As the song progresses and the man seems unmoved, the incredulous pleas ascend to an anguished climax:

I drink the rain

I eat the sun

I give the breath that fills your lungs

I hear the roaring engines thrum

But I cannot run

As individuals, trees have limited defense mechanisms. Some release toxins to change the taste of their leaves, making them less appealing targets. Holly preyed on by herbivores will grow its leaves back spiky to discourage further assault. But these sorts of tricks get only so far. A tree’s true strength lies not in its private arsenal but in its many defensive pacts made with other species.

To the casual glance, a tree is more a site of rest than action. Trees seem to do very little; they merely exist and imperceptibly grow. In this case, the first impression is entirely misleading. Trees exist in a constant struggle, in which the illusion of peace is preserved by a balance of powers that would make the European powers of centuries past blush. A tree is a metropolis, each hosting thousands of species that may be friendly or hostile.

Down in the roots, the war wages on a microscopic level. The tree secretes sugars and hormones into the soil to entice beneficial microbes, such as the fungi mentioned above. But such a rich display of wealth is sure to attract interlopers. Herbivorous beetles, such as weevils, begin as larvae in the tree’s root system. Scarab beetles, far from the flesh-devouring swarm portrayed in The Mummy (1995), like to gnaw on roots and also on the waste of other underground creatures. Beetles like these would devour the tree’s roots, were it not for defenders such as digger wasps. These parasitic wasps inject the beetles with their larvae. Upon hatching, they consume the beetles from the inside.

Moving upward, the trunks of trees conceal the many miniature drama happening moment by moment. Between the tree’s heartwood and its rough exterior bark lies the tender cambium. This layer represents the tree’s future growth; its nutrient rich cells are therefore a target.

Horntails or “wood wasps,” termites, certain ants, and beetles beyond number all have ways of circumventing the exterior bark and gaining access to a tree’s rich interior. To counteract this threat, a tree under assault secretes volatile chemicals into the air, attracting predatory insects of these invasive species. The tree also keeps up a larger security force. Nuthatches and woodpeckers prowl, vigilant against insects seeking entrance into the bark. The minor damage caused by a woodpecker is usually more than worth the services provided, often catching infestations before they grow beyond count.

Finally, in the leaf canopy we meet the creatures most accessible to human observation. It makes sense why leaves would be such a delicacy to herbivores. One the one hand, that’s where photosynthesis renders sunlight and carbon dioxide into nourishing sugars. On the other, trees respirate through their leaves, releasing oxygen and water. Leaves are also easier to eat than wood.

Here the most prominent aggressors are caterpillars, the larval forms of moths and butterflies. Despite their harmless appearance (except when magnified!), they appear in numbers and can be a menace. A single royal silkworm moth larva can consume 40 to 50 leaves in preparation for cocooning. While we’re accustomed to seeing the holey leaves of trees hosting caterpillars, some species of caterpillars are smart enough to hide their work by biting through the stem of a leaf they’ve chewed on.

But here again, the tree hosts predators. Many common backyard birds—robins, wrens, thrushes, chickadees—feast on caterpillars. Jumping spiders are among the tree’s best defenders. They consume not only caterpillars but other tree pests such as lace bugs and leafhoppers. Perhaps the most dramatic caterpillar predator is the assassin bug, a patient hunter that stalks slowly and strikes suddenly.

This woodland circle of life may be less cinematic than mammals hunting on the African savannah, but its stakes are no lower. A tree is a savvy political strategist, offering sap, shelter, and sometimes parts of itself to ensure the continued cooperation of a host of allies against determined thieves and invaders.

4. Disruption Does Not Mean Death

On a late winter morning, a woodsman saws at a hazel tree. He severs its trunk low, mere inches from the ground. The bushy tree crashes to the ground, and he hauls it away. Around him other woodsmen are doing the same, clearing the ground. Is it the end for the hazel grove?

Hardly. Bereft of its leaves, the tree has no way to make new nutrients. But the roots have reserves left over for just such a calamity. Immediately the tree will begin to put out new shoots alongside the old trunk. They are thin, but grow quickly, gaining over a foot per year. In just a few years the hazel will be back, bushier than before, but fully functioning. Preferably before the shoots begin to thicken, the cycle can be repeated.

This technique, coppicing, has been employed since prehistoric times. Because coppice trees tend to provide a large amount of thin, flexible wood of a similar thickness, they are perfect for firewood and for weaving into wattle panels. In pre-industrial time, before nails were mass-produced, these woven wood panels served as fencing and in building construction.

Trees that cannot rely on their own stored resources may be saved by others. Peter Wohlleben recounts stumbling across a patch of mossy stones in a forest under his management. Upon further inspection, he found that they weren’t stones at all, but wood. Green, living wood! The stones were stumps from an old beech tree, and they were being kept alive by the surrounding beeches, through the fungal network discussed above. For hundreds of years they lived on the charity of the other trees.

The resilience of trees is astounding. In the Dalarna province of Sweden stands Old Tjikko, a Norway spruce surrounded by shrubby brush. All of this is in fact connected to a single root system estimated to be over 9,500 years old. The visible part of the tree can last only 500 or 600 years, but when it inevitably meets its end, the roots push up new shoots, and the cycle begins again.

The closer we look at anything, the more unfamiliar it appears. As with a circle, the surface is only a fraction of the total area. If there is wisdom to be found in trees, we shouldn’t expect it to be immediately obvious. Thankfully, the trees are in no rush, and if we have the courage to resist the demands of our “burnout society,” neither are we.

The trees speak slowly. To hear what John Muir called the preaching of pine trees, to learn the rituals of what J. Drew Lanham called swamp religion, we’ll have to turn both the inquisitive eye and the generous heart toward our strong, silent neighbors. I end here with a quote from James Nardi on the neighborliness of trees; I wonder what it would mean to be neighborly in return.

Trees are gracious and neighborly. Their forms muffle noises as well as add cheer and beauty to a landscape. They hold moisture in the soil, and they also protect it from erosion. With their roots, trees pull up mineral nutrients from deep in the soil that will be shared with other creatures in their communities. They absorb carbon dioxide and many pollutants from air. Each year when they shed their leaves, trees return many nutrients to the soil to replenish the fertility of the land. Trees offer nourishment and refuge to all visitors and companions. In the cold of winter, they block icy winds …. In the heat of summer, they provide coolness and shade …. Urban trees can reduce summer temperatures as much as 6.5°F…. When the collective transpiration of trees in a forest condenses as clouds, air containing the transpired vapor condenses and decreases in volume, resulting in reduction of air pressure. As the air pressure drops, air with less moisture is horizontally drawn in and generates winds that cool the landscape.

In the 1980s, the Internal Family Systems model of pyschotherapy argued that the mind can be viewed for therapeutic purposes as a network of subpersonalities, each with their own viewpoint and agenda. The goal was integration of these parts with the core self. They used terms like “exiles,” “managers,” and “firefighters.” I like Sandburg’s schema better.

Published in 1849, this poem (available from the Poetry Foundation) preceded Darwin’s Origin of Species.

On the relationship between trees and humans from prehistoric times to today, I have drawn from Roland Ennos, The Age of Wood.