Too many people are going to university, and for all the wrong reasons. Once they arrive, they find themselves cogs in a machine, designed to produce not cultured, inquisitive minds—heaven forbid!—but docile laborers and functionaries. The point, after all, is to find a job. You may as well rush the process; all employers care about is the diploma. Don’t think about your work; just do it. And the teachers? Pity the teachers. They mean well, but they’re overworked. They sit in overstuffed classrooms, overloaded by bureaucracy. They teach to the lowest common denominator, which gets lower every year, as college becomes a mandatory hoop that every young person begrudgingly flings themself through.

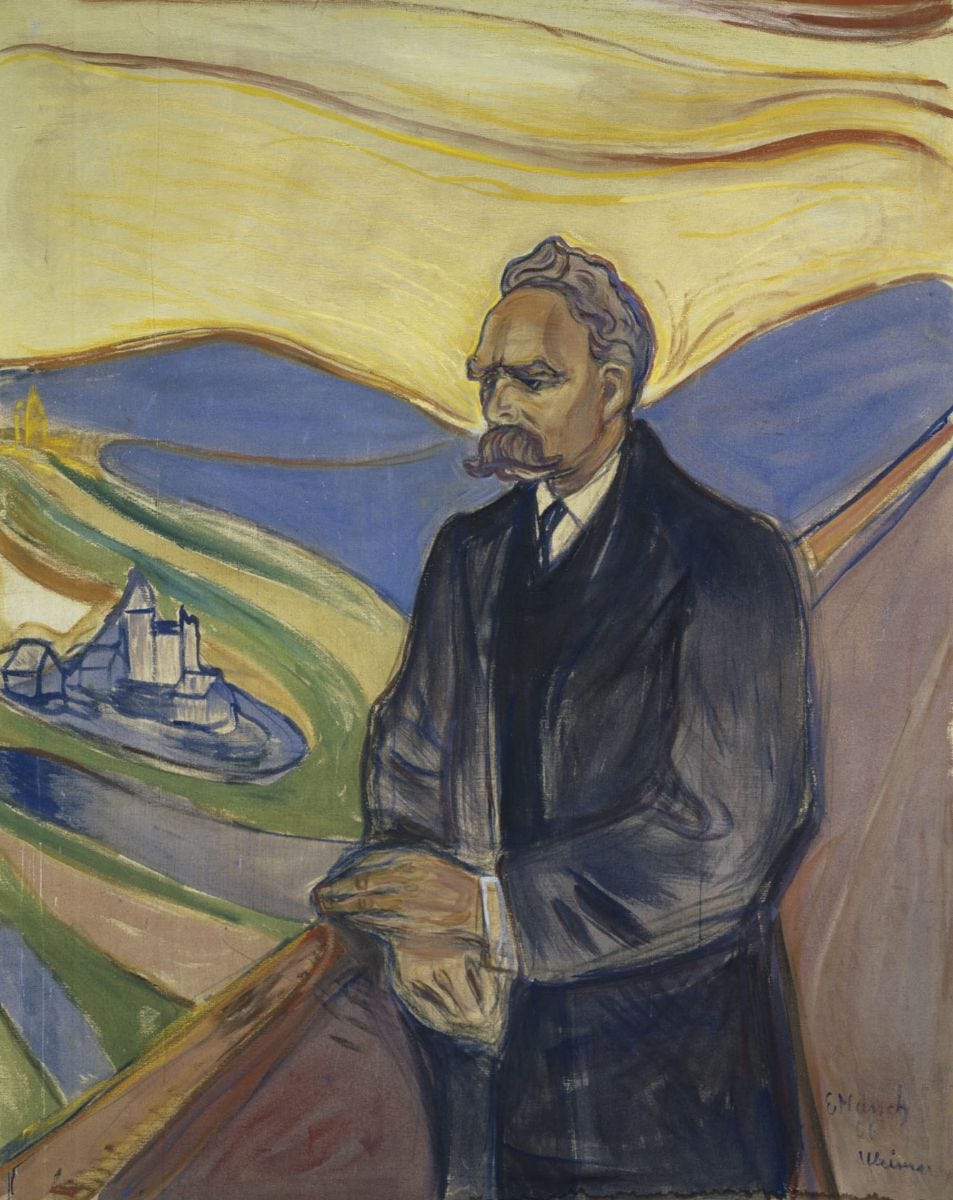

Does the rant above sound familiar? It’s the sort of thing I’ve seen off and on in outlets like the Chronicle of Higher Education. Or from long-tenured humanities professors, equally resentful of the rise of STEM and the critique of “Western civilization.” But this particular rant isn’t from this century or the one before. It is a paraphrase of a passage from Friedrich Nietzsche’s 1888 work The Twilight of the Idols.

Having said that, I don’t really want to talk much about the modern university. There are complicated historical and social reasons for why educational policy is a frustrating topic. Mostly they have to do with an abundance of stakeholders (future employers, government, parents, students, admin, faculty, etc.) with unclear and even conflicting interests.

Here I want to focus on one complaint only, the sense that our educational institutions aren’t preparing students to live satisfying intellectual lives. This is a goal that comes into clear conflict with the pragmatic purpose of education, credentialing people for specific jobs:

There is such an oppressive and indecent sense of hurry, as if something would be lost if a twenty-three-year-old is not ‘finished’ yet, does not have an answer to the ‘ultimate question’: ‘what job?' what calling?’ — Higher types of humans, if I may say so, have no love of ‘callings’, for the very reason that they know that they have been called … They have time, they take their time, they never think about being ‘finished’,—the way a high culture sees things, when you are thirty you are just a beginner, child.

What is this higher type of human? How have they been called? What is taking so much time? Nietzsche doesn’t clarify in this passage, but the ideas refer back to The Gay Science. There he complains that most people say they follow their conscience, but what that really means is that they have uncritically adopted the ideals of their society. They mistake the whispers of others for their own authentic voice.

Instead, he asks, “Do you know nothing of an intellectual conscience? A conscience behind your ‘conscience’?” He calls on people to recognize how their opinions and even desires are shaped by their history. If we are trapped in the dream, he wants to create lucid dreamers. “We … seek to become what what we are—human beings who are new, unique, incomparable, who give themselves laws, who create themselves!”

Although Nietzsche continues to speak in terms of formal education, it seems clear that no real institution that takes money to run and answers to stakeholders could ever devote itself exclusively to what he deems this higher calling of life.

Nietzsche’s School of Culture and Creativity

But let’s imagine a Nietzsche’s School of Culture and Creativity. Anyone of intellectual ambition can get an invitation via raven and board a magical train to Basel. They get free room and board. They get sorted into houses: Wagner, Goethe, Schopenhauer, or (for the bad apples) Kant. What exactly happens next?

Nietzsche: “I will immediately put forward the three tasks that require an educator. People must learn to see, they must learn to think, they must learn to speak and to write: the goal in all three cases is a noble culture.”

Is that really a curriculum? How are teachers supposed to make lesson plans around that? Really, these sound more like fundamental dispositions, character traits that people have to develop on their own. Then again, when I think back over my time in school, I recall moments when certain teachers somehow reached me. They managed to get my attention off of whatever concrete piece of information was being discussed and turn it back onto myself, onto my habits of noticing, thinking, judging, framing, communicating. In the aftermath of these interactions, I felt less like I had learned a discrete bit of information and more as if my mind and soul had expanded in a permanent and exciting way. Indeed, I have often tried to do the same with my students. So, a kind of virtuoso educational performance can result in a transformative encounter, but it seems impossible to standardize it for every teacher, every student.

When we ask Nietzsche what it means to see, we get a surprising answer. For him, at least in this passage, the opposite of sight is not obliviousness, but premature judgment.

Learning to see — getting your eyes used to calm, to patience, to letting things come to you; postponing judgment, learning to encompass and take stock of an individual case from all sides. This is the first preliminary schooling for spirituality: not to react immediately to a stimulus, but instead to take control of the inhibiting, excluding instincts. Learning to see, as I understand it, is close to what an unphilosophical way of speaking calls a strong will: the essential thing here is precisely not ‘to will’, to be able to suspend the decision. Every characteristic absence of spirituality, every piece of common vulgarity, is due to an inability to resist a stimulus—you have to react, you follow every impulse. In many cases this sort of compulsion is already a pathology, a decline, a symptom of exhaustion,—almost everything that is crudely and unphilosophically designated a ‘vice’ is really just this physiological inability not to react.

Nietzsche often proudly referred to himself as a “psychologist.” By this he meant someone who can see beyond justifications to understand the real reasons people speak and act the way they do. In fact, he came to see psychological insight, or reflexive self-awareness, as at the heart of intellectual development.

When Nietzsche speaks here about resisting impulses, he isn’t primarily thinking of moral vices such as lust, greed, compulsive behaviors. These for him were symptoms of more universal afflictions. Earlier in Twilight he identified a human propensity toward the “error of imaginary causes” in which people, desperate to construct narratives that explain their experiences, uncritically adopt whatever is at hand. In a moment of unusually straightforward and relatable prose, he lays out the entire process:

Familiarizing something unfamiliar is comforting, reassuring, satisfying, and produces a feeling of power as well. Unfamiliar things are dangerous, anxiety-provoking, upsetting, — the primary instinct is to get rid of these painful states. First principle: any explanation is better than none. Since it is basically a matter of wanting to get rid of unpleasant thoughts, people are not exactly particular about how to do it: the first idea that can familiarize the unfamiliar feels good enough to be ‘considered true’.

As Nietzsche envisions it, this process is at work broadly. Not only do individual sensations and events get explained this way, but phenomena can be grouped together into a single explanatory network. With each successive “successful” explanation, a positive feedback loop is established, leading to a dominant explanation. To challenge this would appear not only absurd, but also threatening.

Unsurprisingly, Nietzsche identifies religion and morality as the prime examples of this development. Why do I feel bad? Because I’ve sinned. In this case, the explanation also comes with a social script to get rid of the bad feeling. It works, so I adopt the system. Now someone tells me my explanation is wrong. This makes me feel bad. And how have I learned to identify bad feelings? Exactly, as sin. Now I know that questioning the system is sin. It’s no easy task to dethrone a dominant explanation.

Returning to Nietzsche’s prescriptions for education, what does seeing properly look like?

A practical application of having learned to see: your learning process in general becomes slow, mistrustful, reluctant. You let foreign things, new things of every type, come towards you while assuming an initial air of calm hostility, — you pull your hand away from them. To keep all your doors wide open, to lie on your stomach, prone and servile before every little fact, to be constantly poised and ready to put yourself into — plunge yourself into — other things, in short, to espouse the famous modern ‘objectivity’ — all this is in bad taste, it is ignobility par excellence.

All this reminds me of the wary self-assuredness of a cat. Sometimes a cat desires your company; it doesn’t need it. The more you seek to entice it, the more suspicious it becomes. But in fact, Nietzsche’s guardedness comes from a lack of confidence. He sees the self as a willing collaborator with the bad actors in society, all too eager to trade away its responsibility to think for itself in exchange for whatever narrative they’re selling.

The difficulty, the denial involved in keeping a noble disposition toward the world is expressed in another treatise written around the same time, Ecce Homo: “How much truth can a spirit tolerate, how much truth is it willing to risk? This increasingly became the real measure of value for me…. Every step forward in knowledge comes from courage, from harshness toward yourself.” What exactly does this harshness toward self consist in? Not the hair shirts and fasting of medieval penitents. Rather, the realization that for every question, the true answer is probably not the answer my unconscious drives are nudging me to prefer. When these two do coincide, it is a coincidence, not a feature of reality.

As an educator, I find this subversion of pedagogical priorities titillating. In faculty meetings around the world, teachers brainstorm ways to render students more receptive: “How do we get them to listen to us?” Nietzsche worries about the reverse. How do we get them to question us, to depart from the easy path of learning what the teacher wants to hear and docilely parroting it for points? I don’t know that I have enough courage, enough harshness toward myself, to instill in my students a more critical attitude toward me. But also, how do we get them to question themselves? Teaching them to mistrust certain facets of their own psychology is a tricky business, not one that I feel qualified to take on at scale.

The last passage may leave the impression that thinking was a dour, anxious thing for Nietzsche. Despite his comments about being on guard against explanatory narratives, what jumps out to any reader of Nietzsche is his joy, his playfulness in examining ideas from various points of view. He turns them on their head, he shakes them to see what falls out, he strips them of their guises only to clothe them in others—a philosopher playing dress-up!

One of his best analogies for thinking as both a methodical activity and a playful, graceful one is dancing. In fact, he describes the educator’s second task, teaching people to think, as instructing dance:

Learning to think: our schools do not have any idea what this means. Even in the universities, even among genuine philosophy scholars, logic is beginning to die out as a theory, a practice, a craft. Just look at German books: there is not even a dim recollection of the fact that thought requires a technique, a plan of study, a will to mastery, — that thinking wants to be learned like dancing, as a type of dancing…. A noble education has to include dancing in every form, being able to dance with your feet, with concepts, with words; do I still have to say that you need to be able to do it with a pen too — that you need to learn to write?

At this point Nietzsche breaks off. We are left with little instruction in the art of speaking or writing except for the insistence that these too are forms of dancing. The overall tone of this section of Twilight of the Idols is negative, a grumbling against the educational system. It seems implausible that any school system could meet Nietzsche’s standards.

Where does that leave us? What if we, too, feel in various ways that we have been insufficiently formed by our formal education? Is there any place we can go, any teacher we can hire to instruct us to see and think and dance correctly? I believe there is. I have been moved by a Japaneses novelist who sees with uncanny precision, who think in unpredictable leaps, who dances with his pen: Haruki Murakami.

Haruki Murakami on Self-Schooling

Haruki Murakami is one of Japan’s most widely-read authors. His simple prose beguiles the reader into worlds of imagination. His characters, sometimes unusual but always fully realized, navigate environments that run from those lightly tinged with the supernatural to bizarrely surreal.

When I learned that Murakami had published a book of essays about writing, I leapt at it. What’s the secret behind the magic? What strange upbringing or vagaries of circumstance created Murakami’s weird and wild mind?

Unfortunately, right off the bat, Murakami tempers expectations: “One thing I do want you to understand is that I am, when all is said and done, a very ordinary person.” He keeps this apologetic, aw-shucks attitude through most of the book. In fact, he seems worried that he’s disappointing people by being too normal, no debauched Byron or adrenaline-addict Emerson. “I have the sense that no one is hoping that a writer lives in a quiet suburb, lives a healthy early-to-bed-early-to-rise lifestyle, goes jogging without fail every day, likes to make healthful vegetable salads, and holes up in his study for a set period every day to work.”

On second look, however, interesting patterns emerge. Murakami emerges as someone who is unusually open to experience while also resistant to social pressure. He remarks that most people who grew up in his situation went to university, found a job, then married. He did it in the reverse order. He’s a cat person, by which he means he finds it difficult to take orders or pretend enthusiasm for things he doesn’t care about. Early in life he never considered writing for a career, but he knew he wouldn’t be happy as a company man, taking orders. Instead, he opened a jazz cafe, where he could be his own boss and listen to the music he liked all day long.

Much like Nietzsche, he cautions against quick, moralizing judgments of others, seeking rather simply to notice them. But he also has an unshakable trust in his own deeply felt intuitions. This becomes clear in the story of how he became a writer. At 29 years old, he went to watch a baseball game. In the aftermath of the satisfying crack of the first hit of the game, the idea I think I can write a novel floated down to him from the sky. He caught it, then after the game went out and bought a pen and manuscript paper. He sat down at his kitchen table and began to write the novel that launched his career.

Where did he learn to write a novel? What prepared him for this moment? For the most part, not school. He claims he never liked school and felt mostly relief at graduating university. He felt that Japanese schools placed too much focus on competition, on rote memorization, on exams. The human, or perhaps humane, element was missing. “I can’t help but thinking that in almost every subject, Japan’s educational system fundamentally fails to consider how to motivate each individual to improve their potential.”

Academic achievement felt artificial, unreal, insignificant to him. What felt real was books and music, passions that eventually became his life’s work. On the power of books, I let Murakami speak for himself:

In my own case, when I look back to when I was in school, the biggest saving grace for me was having some close friends, and reading tons of books. When it came to books, I greedily devoured a wide range, like I was busily shoveling coal into a blazing furnace. I was so busy every day enjoying one book after another, digesting them (in many cases not properly digesting them), that I didn’t have any time left to think about anything else. Sometimes I think that might actually have been a good thing for me. If I had looked at the situation around me more, thought deeply about the unnatural, contradictory, and deceitful things there and plunged right into pursuing things I couldn’t accept, I might have been driven into a dead end and suffered because of it.

Also, reading so widely helped to relativize my point of view, and I think that was very significant for me back when I was a teenager. I experienced all the emotions depicted in books almost as if they were my own; in my imagination I traveled freely through time and space, saw all kinds of amazing sights, and let all kinds of words pass right through my very body. Through all this, my perspective on life became a more composite view. In other words, I wasn’t gazing at the world just from the spot where I was standing, but was able to take a step back and take a more panoramic view.

If you always see things from your own standpoint, the world shrinks. Your body gets stiff, your footwork grows heavy, and you can no longer move. But if you’re able to view where you’re standing from other perspectives—to put it another way, if you can entrust your existence to some other system—the world will grow more three-dimensional, more supply. And I believe that as long as we live in this world, that kind of agile stance is extremely important. In my life this has been one of the biggest rewards of reading. If there hadn’t been any books, or if I hadn’t read so many, I think my life would have been far drearier.

For me, then, the act of reading was its own kind of essential school. A customized school built and run just for me, one in which I learned so many important lessons. A place where there were no tiresome rules or regulations, no numerical evaluations, no angling for the top spot. And, of course, no bullying. While I was part of a larger system, I was able to secure another, more personal system of my own.”

Murakami, despite declaring himself a cat person, seems much less catlike than Nietzsche. Whereas Nietzsche spoke of wariness toward ideas, young Murakami plunged himself into book after book, drowning himself in feelings. But perhaps this amounts to much the same thing. If Nietzsche cautioned against being absorbed by a powerful narrative, Murakami immunized himself against fanaticism by repeatedly subjecting himself to it.

In both cases, it comes down to mental dancing. Nietzsche thought more in terms of a particular method, whereas Murakami imbibed principles organically through volume of exposure. Both found a way to fashion an authentic self capable of imaginative thought. Both resisted the pressure of social norms in their own lives and critiqued elements of their society.

My own formal education, at least parts of it, was quite rewarding. But no institution, however well designed and staffed, can take a person all the way to achieving Nietzsche’s command: “Become who you are.” At some point, each of us must assume responsibility for being our own guide, our own teacher. We must take our unconscious drives in hand. We must dance, even though the whole world is watching.

I love the passage about being able to resist stimuli. Very close to Buddhist mindfulness - being aware of reactions, reacting with intentionality rather than instinct.

This was a worthwhile read. On the background of Nietzsche's "school for free spirits," I wonder if you might enjoy reading _Nietzsche's Journey to Sorrento_ (by Paolo D'Iorio, translated by Silvia Mae Gorelick), specifically Ch. 2, "'The School of Educators' at the Villa Rubinacci." It gives some idea of what this unrealized alternative to Basel might have been meant to look like, had it ever progessed beyond the page. Anyway, as a fellow educator, your piece resonated with me on multiple levels.